Pediatricians and dental professionals have utilized prescription fluoride tablets and drops for decades. Yet, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed to remove them from the market, citing concerns that they may alter the gut microbiome. Further concerns mentioned by the FDA include that fluoride may cause thyroid disorders, weight gain, and decreased IQ. The FDA aims to finalize its safety review, public comment period, and take appropriate action on the removal of pediatric ingestible fluoride prescription drug products by October 31, 2025.1

The American Dental Association (ADA) and American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) have released statements in strong opposition to these actions.2,3 The advantages of these prescription fluoride supplements are well documented. A key benefit of this option is its voluntary nature. No one is being forced to purchase or take fluoride supplements. This contrasts with the long-standing argument against community water fluoridation, which ‒ while also safe and effective ‒ has been criticized as “forced.” Ingestible fluoride prescription drugs thus offer a non-compulsory, viable, safe, and effective option for parents seeking additional protection for their children with high caries risk.

Fluoride Supplementation Review

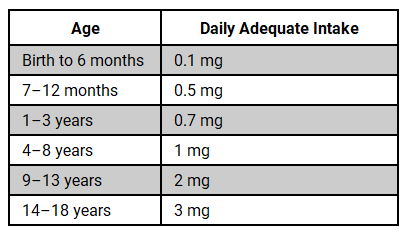

Adequate intakes (AIs) of fluoride and other nutrients are developed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board. The recommended daily AIs for fluoride are established to both optimally reduce dental caries and prevent adverse effects such as dental fluorosis, and these recommendations vary by age.4

The AIs for fluoride in children by age are as follows:

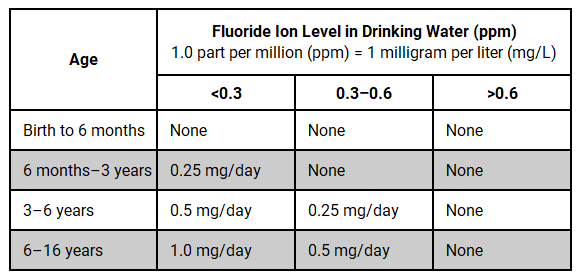

Ingestible fluoride prescription drugs may be indicated for children aged 6 months to 16 years who are at a high risk for caries and reside in areas with low fluoride levels in their primary drinking water.4,5 Conversely, they are not recommended for children living in areas with adequate water fluoridation. A dentist or physician must prescribe all fluoride supplements.5

The appropriate dosage is determined by the child’s age and the fluoride concentration present in their drinking water.5 When prescribing, all sources of fluoride should be evaluated, especially water, as fluoride exposure may occur beyond the home water supply at school and/or daycare. When the fluoride concentration in drinking water is uncertain, testing the water for its fluoride content is recommended before prescribing. For children under the age of 6, the caries risk without fluoride supplements, the benefits of supplements in preventing decay, and the potential for fluorosis should be carefully weighed.5

The recommended daily fluoride supplement dosages based on age and the fluoride concentration in the child’s primary drinking water are as follows:4,5

Studies show that the use of ingestible fluoride prescription drugs during childhood can reduce caries incidence. A Cochrane Review, for example, found a 24% reduction in permanent teeth. A systematic review further reported reductions of 48%–72% in primary teeth, with some trials extending to 6–10 years of monitoring showing a 33%–80% reduction in caries incidence in children aged 7–10 years.4

Evaluating the FDA’s Concerns

The real question is: Are the FDA’s concerns valid? They cite several studies to support their assertion for the need to re-evaluate the safety of ingestible fluoride prescription drugs.1 Let’s discuss what these studies tell us.

Water Fluoridation

The study cited on community water fluoridation is not applicable to the FDA’s current action because it is not attempting to halt community water fluoridation. Rather, the agency’s focus is specifically on removing ingestible fluoride prescription drugs from the market.1,6 Therefore, we cannot extrapolate the effects of community water fluoridation to apply to these ingestible drugs. While a child’s fluoride exposure from community water fluoridation is a critical factor in a physician’s or dentist’s decision to prescribe these supplements, the FDA’s current action is based on research that studies the effects of community water fluoridation as a whole, not the targeted, voluntary, and dosage-controlled use of prescription fluoride drugs. Although the study found that community water fluoridation did indeed lower dental caries rates, it still does not address the pros and cons of ingestible fluoride prescription drugs.6

Furthermore, the objectives and study questions did not assess any adverse health outcomes mentioned in the FDA’s news release.1,6 The only adverse outcome evaluated in this study was dental fluorosis. Consequently, its relevance can be dismissed.6

Fluoride and IQ Scores

I have previously written about the persistent claim that fluoride ingestion lowers IQ scores.7 Most of the research on IQ levels in children and fluoride is based on water fluoridation. Again, this is an issue with extrapolating findings to apply to ingestible fluoride prescription drugs because it’s a different fluoride exposure method. Even so, let’s discuss the systematic review and meta-analysis on water fluoridation cited by the FDA to support their concerns about ingestible fluoride prescription drugs.1,8

The first thing I want to highlight about this study is that it states, “To our knowledge, no studies of fluoride exposure and children’s IQ have been performed in the United States, and no nationally representative urinary fluoride levels are available, hindering application of these findings to the US population.”8

This further undermines the relevance of this study because it not only tests an entirely different fluoride exposure method but also lacks applicability to the United States. Despite these serious limitations, let’s examine the findings.

This systematic review and meta-analysis established a dose-response relationship between fluoride exposure and children’s IQ levels.8 The dose-response relationship measures the effect of a substance’s dose, which can be either therapeutic or toxic.9 Initial findings from the overall study data suggested there was uncertainty about the relationship between IQ and water fluoride levels below 1.5 mg/L. Nevertheless, when focusing on higher-quality studies, a subtle but consistent decrease in children’s IQ was noted even at these lower concentrations. This effect was modest: for every 1 mg/L increase in urinary fluoride, a decrease in IQ between 1.14 and 1.63 points was observed, depending on the study quality.8

Critically, these doses are well above the regulated community water fluoridation exposure in the United States, which is 0.7 mg/L (0.7 ppm). This exposure is also much higher than any exposure typically associated with ingestible fluoride prescription drugs.4,5

While it is essential to consider the combined effect of all fluoride sources, a physician or dentist is trained to do so. They determine the correct dosage of ingestible fluoride prescription drugs based on the individual patient’s total fluoride exposure, thus decreasing the risk of adverse effects from a combination of sources.5

Furthermore, the authors themselves identified that most of the studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis had a high risk of bias (52 out of 64).8

Thyroid Disorders

The FDA cites a systematic review and meta-analysis to support the claim that prescription ingestible fluoride drugs may cause thyroid disorders.1,10 This claim has also been a long-standing focal point of arguments against community water fluoridation. Like the fluoride and IQ study discussed previously, this research is also being used by the agency to extrapolate findings to ingestible fluoride prescription drugs.

The study found that high levels of fluoride exposure can contribute to increased levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Specifically, for water fluoride, TSH concentrations began to rise around 2.0 mg/L in the overall analysis, or above 2.5 mg/L when focusing on studies of the highest methodological quality. These concentrations are primarily associated with naturally occurring high fluoride in drinking water.10 Again, these levels are well above the doses used in community water fluoridation in the United States and well above the doses a child would be exposed to via ingestible fluoride prescription drugs.4,5

While a clear dose-dependent increase in TSH associated with drinking water was observed, the study was unable to confirm a distinct association for circulating thyroid hormones (T3 and T4). Furthermore, the available evidence regarding the risk of thyroid disease (such as goiter or hypothyroidism) was too limited for the study to draw definitive conclusions, although some indication of detrimental effects was noted at the highest observed fluoride levels.10

Gut Microbiome

The FDA’s primary concern in its decision to remove ingestible fluoride prescription drugs from the market is that “ingested fluoride has been shown to alter the gut microbiome.”1 They cite two systematic reviews and meta-analyses to support their concerns.1,11,12

The first systematic review found a significant gap in human studies examining the effects of ingested fluoride on the gut microbiome. Consequently, it reported only one ex vivo study that assessed the impact of fluoride on human gut microbiota. The other studies included in the review were based on the effects of topical fluoride on the oral microbiome. Nevertheless, studies included in this systematic review consistently reported limited to no adverse effects on the oral microbiome from topical fluoride, and in some instances, suggested beneficial outcomes.11

The single ex vivo study that assessed the effects of fluoride on the gut microbiome found that low levels of fluoride exposure, 1–2 mg/L, had little or possibly beneficial effects on the gut microbiome. These doses increased beneficial bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium and Lactobacillus. While high levels, 10–15 mg/L, had adverse effects by reducing beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiome.11

The second systematic review provided a broader search for human studies, identifying four studies that touched upon fluoride’s impact on the human gut microbiome. Of these, only one ex vivo study, which was also included in the first systematic review, directly assessed the effects of fluoride on human gut microbiota. The remaining human studies examined correlations with long-term exposure to high levels of naturally occurring fluoride leading to fluorosis or the use of specific medical imaging agents. This review similarly concluded that low doses of fluoride (1–2 mg/L) did not cause significant changes in the gut microbiome and may even support beneficial bacteria.12

This research consistently demonstrates a dose-response relationship for fluoride’s effects on the microbiome. Therefore, using evidence of high-dose effects to claim harm without acknowledging beneficial or neutral effects at lower, recommended doses could lead to an incomplete understanding of fluoride’s complex impact on the gut microbiome.12

Understanding Drug Safety: Dose-Response Relationship

The dose-response relationship is a fundamental concept for all medications, but its application to fluoride is likely not well understood by patients. For example, the maximum therapeutic dose of acetaminophen for adults administered orally is 1000 mg every 4–6 hours, with a maximum daily dose of 4000 mg. Taking more acetaminophen than recommended can result in severe liver damage.13 Yet, no one is suggesting we remove acetaminophen from the market, because we know there is a safe and beneficial dose. This concept is often ignored when considering fluoride.

Furthermore, the mechanism of action of acetaminophen is still not well understood, whereas the mechanism of action of fluoride is well documented. We genuinely have a better understanding of how fluoride works than we do of acetaminophen.14,15

In Closing

With the push to remove community water fluoridation and the removal of ingestible fluoride prescription drugs from the market, there is potential to see increased caries incidence and prevalence. This means that dental professionals will need to be more diligent than ever in providing oral hygiene instructions, nutritional counseling, and patient education on the use, safety and effectiveness of topical fluoride.

Providing optimal patient care is already a challenge, and the public’s misunderstanding about fluoride is only adding to the barriers we face. As dedicated preventive specialists in oral healthcare, these barriers are no match for our knowledge and passion for oral health. The recent attacks on fluoride are disheartening, but they also present a unique opportunity. With a proper understanding of the science, dental hygienists are in a unique position to combat misinformation from their operatories, and in doing so, not only help improve oral health literacy but also enhance patient outcomes.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, May 13). FDA Begins Action to Remove Ingestible Fluoride Prescription Drug Products for Children from the Market [Press release]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-begins-action-remove-ingestible-fluoride-prescription-drug-products-children-market

- American Dental Association. (2025, May 13). Statement from the ADA on FDA Action to Remove Ingestible Fluoride Prescription Drug Products [Press release]. https://www.ada.org/about/press-releases/statement-from-the-ada-on-fda-action-to-remove-ingestible-fluoride-prescription-drug-products

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. (2025, May 13). ADHA Issues Statement on FDA Action Regarding Ingestible Fluoride Prescription Products [Press release]. https://www.adha.org/newsroom/statement-fda-action-removes-ingestible-fluoride/

- Fluoride: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. (2025, April 11). National Institute of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Fluoride-HealthProfessional/

- Fluoride: Topical and Systemic Supplements. (2023, June 14). American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/fluoride-topical-and-systemic-supplements

- Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z., Walsh, T., Lewis, S.R., et al. Water Fluoridation for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024; 10(10): CD010856. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010856.pub3/full

- Hatfield, S. (2024, October 16). Giving Perspective on the Recent Report on Water Fluoridation and Cognitive Impairment. Today’s RDH. https://www.todaysrdh.com/giving-perspective-on-the-recent-report-on-water-fluoridation-and-cognitive-impairment/

- Taylor, K.W., Eftim, S.E., Sibrizzi, C.A., et al. Fluoride Exposure and Children’s IQ Scores: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025; 179(3): 282-292. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11877182/

- Gupta, P. K. (2016). Fundamentals of Toxicology. Elsevier.

- Iamandii, I., De Pasquale, L., Giannone, M.E., et al. Does Fluoride Exposure Affect Thyroid Function? A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Environ Res. 2024; 242: 117759. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S001393512302563X

- Moran, G.P., Zgaga, L., Daly, B., et al. Does Fluoride Exposure Impact on the Human Microbiome?. Toxicol Lett. 2023; 379: 11-19. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037842742300098X

- Yasin, M., Zohoori, F.V., Kumah, E.A., et al. Effect of Fluoride on Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review. Nutr Rev. 2025; 83(7): e1853-e1880. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12166178/

- Acetaminophen (Oral Route, Rectal Route). (2025, June 30). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/acetaminophen-oral-route-rectal-route/description/drg-20068480

- Gerriets, V., Anderson, J., Patel, P., Nappe, T.M. Acetaminophen. (2024, January 11). StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482369/

- Nassar, Y., Brizuela, M. The Role of Fluoride on Caries Prevention. (2023, March 19). StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587342/