The American Society of Hematology’s publication, Blood Advances, covers hematology and related sciences, including lymphomas, leukemias, hemophilia, and a host of anemias. Unless you struggled with a hematology issue or were a researcher, the journal doesn’t trend on Yahoo or Google.

I did find a study that somehow traveled into my inbox from the journal that piqued my interest. Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) who are privately insured spend approximately 1.7 million on medical expenses over their lifetime.1 That feels like a lot of money to me. It prompted me to realize I know just the basics of a disease that ‒ yes, granted, only 70,000 to 100,000 Americans have SCD. However, it is still the most common form of an inherited blood disorder.2

About one in 12 African Americans carry the autosomal recessive mutation, and approximately 300,000 infants are born with sickle cell anemia annually. People of African descent make up 90% of the population with sickle cell, and the median life expectancy is between 42 to 47 years old.3 You will also find patients of an Asian (Indian), Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, and Hispanic descent having the disease. The commonality is regions of malaria endemicity. To inherit SCD, you must get a gene from both parents. If only getting one defective gene from a parent, patients typically live normal lives without health problems.

During our dental careers, we will surely come across a patient or two stricken with SCD. Digging into the cobwebs of my mind, I knew little about this blood disease or what to look out for as a dental clinician.

What is Sickle Cell Disease?

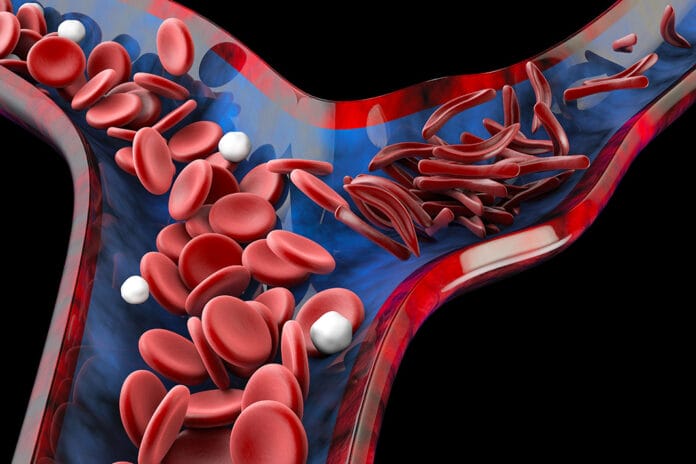

Healthy red blood cells are smooth, round, and bendy, and they can easily drift through blood vessels and bring oxygen to all parts of the body. In sickle cell disease, the cells can change shape to form a crescent and become stiff and sticky. They can catch on to one another and stick to the vessel walls, which makes it difficult to squeeze through tiny blood vessels, and they will break down inside blood vessels. Cells can get piled up and prevent organs from getting the proper amount of oxygen they need. Systemic complications are well documented, including gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, acute chest syndrome, and central nervous system issues.

What about oral complications and considerations?

Oral Manifestations

“There are oral manifestations of sickle cell disease, but they are not specific to the disease.” 4 You could see pale tissue as with all anemias or yellowing, delayed tooth eruption, which is 1.7 times more frequent. In addition, you could see hypomineralization of tooth enamel and dentin, surface cell changes of the tongue, mandibular osteomyelitis, nerve damage to the inferior alveolar nerve, orofacial pain, and pulpal necrosis of healthy teeth.5

The presence of healthy, necrotic teeth is 8.33 times higher in a patient with sickle cell disease compared to a non-sickle cell patient.6 This is due to vascular occlusions of the pulpal microcirculation.7 Remember that many cases of necrosis aren’t painful, and, when looking at dental radiographs, you may see enlarged irregular bone.8

Infection from Sickle Cell Disease

A priority in sickle cell management is the prevention of infection. Infectious complications are common and well documented. Pneumonia is a leading cause of death in infants and young children with SCD.

Nearly 100% of sickle cell anemia patients will develop asplenia.9 Asplenia is the absence of normal spleen function, and the anti-bacterial role of the spleen makes them more susceptible to infections. Interesting note: gram-negative organisms are a cause of infections in sickle cell patients.10 The bacteria associated with periodontal disease are predominately gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. However, most studies do not show a link between periodontal disease and sickle cell.11

The aforementioned study specifically looked at both homozygous (two identical alleles of a particular gene) and heterozygous (two different alleles of a particular gene) and found that only the heterozygous form is correlated with periodontal disease. The authors discussed that the inconsistency was that the density of trabecular bone is decreased by the pathology in heterozygotes, making it more susceptible to the consequences of periodontitis.

The relationship with periodontal disease is conflicting and not researched well enough. There is some research finding that SCD patients have greater periodontal pocket depths than those of their healthy counterparts, which for me, would err on the side of a relationship.12 Other studies stated that there were no differences between patients with SCD and controls regarding probing depths or attachment loss.13-15 Be mindful that the SCD patient can present with gingival enlargement.16

There is not a concrete rule of thumb for antibiotic premedication in patients with SCD, so a consultation with the patient’s physician is warranted. Penicillin prophylaxis in children and widespread use of the pneumococcal vaccine has made fantastic strides in decreasing the rate of bacterial infections and sepsis.17 Premedication may be necessary if the patient has a compromised immunity due to splenectomy, spleen hypofunction, or a low white blood cell count. Medical clearance for dental treatment such as non-surgical periodontal therapy/SRP, including curettage and invasive dental procedures, is recommended.

The only way to cure sickle cell disease is a bone marrow transplant (BMT) which is quite complex. If your patient is receiving a transplant, there will be a request from the patient’s internists, hematologist, or oncologist for an exam looking for oral infections prior to the procedure and specific post-surgery instructions. These instructions may include the use of fluorides, chlorhexidine rinse, interdental cleaning, and dependent upon the platelet count.

Mucositis may present during the bone marrow treatment, and advising patients of helpful treatment prior to would be advantageous. Post transplant patients experience dry mouth and yeast overgrowth for the clinician to keep an eye out for. If a platelet count is below 50,000, dental care should be set at a later date, or in case of an emergency, a platelet transfusion may be required.

As of September 2018, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) launched the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative. Moving forward, new gene therapy has shown promise in both preclinical and clinical trials. The technology will involve removing the patient’s stem cells from the bone marrow and then adding a therapeutic gene to those cells, which will then lead to the production of anti-sickling cells.18

Caries from Sickle Cell Disease

Research has shown no significant difference in the frequency of carious lesions between sickle cell children and healthy controls. The most common dental problem in children about to undergo BMT was tooth decay, often resulting from neglected oral hygiene and poor nutrition. Tooth decay is especially dangerous in children undergoing BMTs because physicians must first suppress their immune systems to reduce the chance of transplant rejection. Therefore, children about to undergo immunosuppression as part of BMTs should have dental checkups.

Still, there is a higher rate of oral fungus found in sickle cell patients.19 There is a partnership between Candida yeast and Streptococcus mutans. S. mutans clings to the surface of teeth using its own biofilm. This triggers Candida to produce its own glue-like matrix, enabling it to hold on to teeth and grow.20

The SCD patient may be on medications containing sucrose, and there is a frequency of complications and hospitalizations that could complicate oral care, driving a higher caries risk. People with sickle cell average 2.5 hospital visits a year, and young adults are more likely to require acute care or repeat hospitalization.21

SCD medications can also cause xerostomia, and having good options at our ready would be helpful. Another conversation to have with the patient’s physician would be the incorporation of xylitol into their diet if the physician doesn’t see a problem with GI issues.22

Other Sickle Cell Disease Considerations

A sickle cell crisis is a reversible, highly painful episode caused by a lack of blood and oxygen to the tissues, also known as a vaso-occlusive crisis. The most common sign is pain that may be dull, stabbing, throbbing, or sharp and seems to come out of nowhere. There may also be breathing problems, dizziness, and headaches.

If a crisis happens in your office, emergency protocols should begin. A vaso-occlusive crisis can be precipitated by stress, and for some patients, that could come from a dental visit.

In 1973, the lifespan of someone with sickle cell disease was 14 years. Thankfully today, we are seeing decades longer. In fact, Miles Davis, an extraordinary composer and musician whom Rolling Stone described as “the most revered jazz trumpeter of all time, not to mention one of the most important musicians of the 20th century,” had SCD and didn’t pass until he was 65 years old.

Observed every year on June 19th is World Sickle Cell Day, shining a light of awareness on the disease. You may see buildings lit in red to commemorate. There is great hope for the future of SCD, and we, too, can help be a shining light for our patients.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Johnson, K.M., Jiao, B., Ramsey, S.D., et al. Lifetime Medical Costs Attributable to Sickle Cell Disease among Nonelderly Individuals with Commercial Insurance [published online ahead of print, 2022 May 16]. Blood Adv. 2022; bloodadvances.2021006281. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006281. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35575558/

- Sickle Cell Disease. (n.d.). American Society of Hematology. https://www.hematology.org/education/patients/anemia/sickle-cell-disease

- Sedrak, A., Kondamudi, N.P. Sickle Cell Disease. [Updated 2021 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482384/

- Chekroun, M., Chérifi, H., Fournier, B., et al. Oral Manifestations of Sickle Cell Disease. Br Dent J. 2019; 226(1): 27-31. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2019.4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30631169/

- Mendes, P.H., Fonseca, N.G., Martelli, D.R., et al. Orofacial Manifestations in Patients with Sickle Cell Anemia. Quintessence Int. 2011; 42(8): 701-709. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21842010/

- Costa, C.P., Thomaz, E.B., Souza S.de F.C. Association between Sickle Cell Anemia and Pulp Necrosis. J Endod. 2013; 39(2): 177-181. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2012.10.024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23321227/

- da Fonseca, M., Oueis, H.S., Casamassimo, P.S. Sickle Cell Anemia: A Review for the Pediatric Dentist. Pediatr Dent. 2007; 29(2): 159-169. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17566539/

- Sickle Cell Disease. (2020, May 5). College of Dental Hygienists of Ontario. https://www.cdho.org/Advisories/CDHO_Factsheet_Sickle_Cell_Disease.pdf

- Kirkineska, L., Perifanis, V., Vasiliadis, T. Functional Hyposplenism. Hippokratia. 2014; 8(1): 7-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25125944/

- Khalife, S., Hanna-Wakim, R., Ahmad, R., et al. Emergence of Gram-negative Organisms as the Cause of Infections in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021; 68(1): e28784. doi:10.1002/pbc.28784. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33128443/

- de Carvalho, H.L., Thomaz, E.B., Alves, C.M., Souza, S.F. Are Sickle Cell Anaemia and Sickle Cell Trait Predictive Factors for Periodontal Disease? A Cohort Study. J Periodontal Res. 2016; 51(5): 622-629. doi:10.1111/jre.12342. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26670655/

- Arowojolu, M.O. Periodontal Probing Depths of Adolescent Sickle Cell Anaemic (SCA) Nigerians. J Periodontal Res. 1999; 34(1): 62-64. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02223.x. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10086888/

- Guzeldemir, E., Toygar, H.U., Boga, C., Cilasun, U. Dental and Periodontal Health Status of Subjects with Sickle Cell Disease.Journal of Dental Sciences. 2011; 6(4): 227-234. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2011.09.008. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1991790211000821

- Passos, C.P., Santos, P.R., Aguia,r MC, et al. Sickle Cell Disease does not Predispose to Caries or Periodontal Disease. Spec Care Dentist. 2012; 32(2): 55-60. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2012.00235.x. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22416987/

- Al-Alawi, H., Al-Jawad, A., Al-Shayeb, M., et al. The Association between Dental and Periodontal Diseases and Sickle Cell Disease. A Pilot Case-control Study. Saudi Dent J. 2015; 27(1): 40-43. doi:10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.08.003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25544813

- Cober, M.P., Phelps, S.J. Penicillin Prophylaxis in Children with Sickle Cell Disease. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 15(3): 152-159. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3018247/

- Tonguç, M.Ö., Ünal, S., Arpaci, R.B. Gingival Enlargement in Children with Sickle Cell Disease. J Oral Sci. 2018; 60(1): 105-114. doi:10.2334/josnusd.16-0796. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29576570/

- Ashorobi, D., Bhatt, R. Bone Marrow Transplantation in Sickle Cell Disease. [Updated 2021 Jul 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538515/

- de Matos, B.M., Ribeiro, Z.E., Balducci, I., et al. Oral Microbial Colonization in Children with Sickle Cell Anaemia under Long-term Prophylaxis with Penicillin. Arch Oral Biol. 2014; 59(10): 1042-1047. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.05.014. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24967510/

- Falsetta, M.L., Koo, H. Beyond Mucosal Infection: A Role for C. Albicans-Streptococcal Interactions in the Pathogenesis of Dental Caries.Current Oral Health Reports. 2014; 1(1): 86-93. doi:10.1007/s40496-013-0011-6. https://sci-hub.se/10.1007/s40496-013-0011-6

- Smith, W.R/, Scherer. M. Sickle-cell Pain: Advances in Epidemiology and Etiology. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010; 2010: 409-415. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.409. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21239827/

- Nayak, P.A., Nayak, U.A., Khandelwal, V. The Effect of Xylitol on Dental Caries and Oral Flora. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2014; 6: 89-94. doi:10.2147/CCIDE.S55761. https://sci-hub.se/10.2147/CCIDE.S55761