When cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is discussed, do you immediately think of dental implant placement, third molar extractions, or sinus lifts? More and more general dentistry and periodontal practices are investing in CT imaging equipment.

The value of the CBCT image cannot be underestimated in terms of application to the daily practice of dental hygienists. Let’s take a look at how to achieve a diagnostic quality image, types of pathology to look for, and how incredibly useful CBCT images are in helping your patients to grasp their oral conditions, especially periodontal disease.

Patient positioning for CBCT is very similar to that of a traditional panoramic radiograph. Always refer to the manufacturer’s instructions for the finer points of positioning, but here are a few general guidelines.

- The patient will bite on the bite block or stick and hold onto the handles as usual.

- The occlusal plane should be parallel to the floor.

- The stabilizing arms on the machine should be engaged firmly on the sides of the patient’s head and on the forehead to ensure the patient’s head does not move. With CBCT imaging, a small amount of movement is the difference between an outstanding diagnostic radiograph and one that is completely useless. For patients with tremors, it can be useful to seat them in a chair to expose the radiograph, as they may be able to be more still in a seated position.

- Patients should be asked to close their eyes, because the natural instinct is to watch the machine move, and this minute movement affects the image.

In a typical scan, the target region starts just below the bottom of the mandible and ends in the maxillary sinus. The goal is to include all apices of all teeth and the entire inferior border of the mandible. In some instances, a different region of imaging is needed, such as the temporomandibular joint, but for the purpose of this article, we will look at the standard projection.

A few types of common pathology that can be readily identified in a CBCT image include periapical abscesses, cysts, fractures of teeth and bone, sinus abnormalities, tumors, bony defects, perio/endo lesions, as well as vertical and horizontal bone loss.

In my clinical experience, I have seen numerous lesions which are not discernible on periapical or bitewing radiographs and are easily visible on CBCT images, especially bony defects and periapical lesions. CBCT is in no way intended to replace two-dimensional radiographs, but when used in a supplemental manner they can provide a level of diagnostics that cannot be matched.

Dental hygienists are not necessarily diagnosing lesions, but we do act in many ways as front-line detectors of abnormalities. We can advocate for our patients, so they receive the proper referrals, biopsies, diagnoses, and treatments they need to address such lesions. If your practice uses CBCT, it is immensely beneficial to seek more in-depth continuing education regarding the evaluation of images.

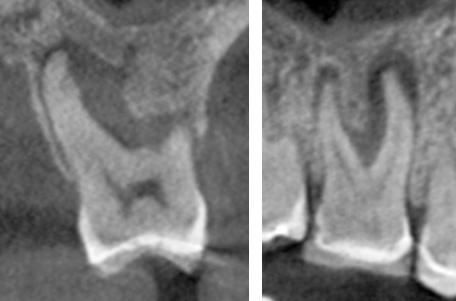

Image 1: Large periapical abscess on #3 that extends up into the furcation. The image on the left is a cross-sectional view with the mesiobuccal root on the left side. The image on the right is a view from the buccal side, with the mesiobuccal and distobuccal roots both visible.

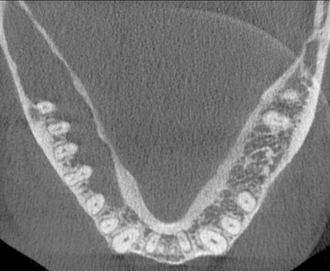

Image 2: View of the mandible reveals a keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Note the lack of trabecular bone on the left side of the image (the patient’s right side) when compared to the opposite side of the mandible.

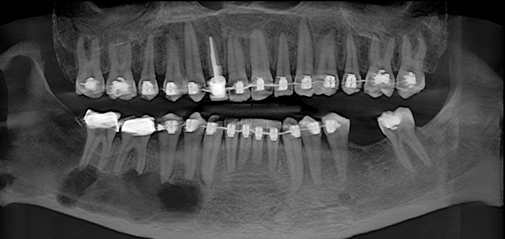

Image 3: Panoramic view of CBCT from the patient with the keratocystic odontogenic tumor seen in image 2.

For daily dental hygiene practice, CBCT images educate patients on their periodontal status. This is invaluable. Even the best hygienist can meet challenges when using generic illustrations of bone loss and periodontal disease in patient brochures or chairside education materials. Patients will have a much easier time owning their condition if they can see the damage in their own mouths.

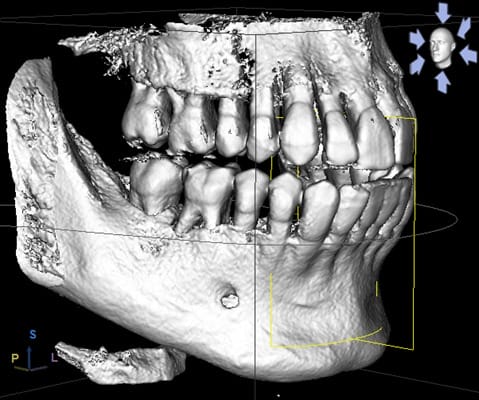

CBCT imaging software can be used not only for three-dimensional slicing but also for viewing the solid surfaces if the maxilla and mandible. The cementoenamel junction (CEJ) is visible in surface mode, as well as the location of the alveolar bone. According to Wilkins, when horizontal bone loss causes distance exceeding 1-1.5mm between the CEJ and the alveolar bone, periodontal disease is present.¹

Image 4: Surface mode image showing bone loss as it occurs in periodontal disease. Note the position of the CEJ in relationship to the alveolar bone, as well as the visible furcation involvement.

Each time a CBCT is taken on a patient, the opportunity should be seized to discuss periodontal health. Furcation involvement can be more clearly seen and evaluated on CBCT than on traditional radiographs, and the patient is more easily able to grasp what the clinician is communicating. The patient can see the furcations and bone loss.

The clinician can explain the needed treatments to stabilize and maintain the periodontal condition. CBCT combined with comprehensive periodontal charting, bitewing radiographs, and photos of the patient’s own mouth provides an all-encompassing educational package for the patient. These records also allow the clinician to answer any arising questions clearly with applicable visual aids that are specific to the patient. Effective communication is key in bridging the gap of patient understanding.

It seems that the two main barriers preventing patients from accepting dental or periodontal treatment are, first, the understanding and acceptance (or owning) of the condition needing treatment and secondly, finances. If the first can be overcome, the patient is more likely to try to find ways to break through the financial wall as well.

As for the safety of CBCT, proper barriers should be used to protect patients, and as with any radiation, the clinician should strive to follow the ALARA principle. A patient who receives a CBCT does not also need a two-dimensional panoramic radiograph since all information that can be gained from a 2D image can also be seen in the CBCT, which helps to limit the need for additional radiation exposure.

Each manufacturer has machine-specific radiation information available. Studies investigating the direct comparison between radiation exposure of panoramic and CBCT images revealed, “the effective dose for panoramic radiography is about 22.0 µSv, and for CBCT examination the effective dose is 61-134 µSv.”² To put that into perspective, each person in the United States is estimated to be exposed to 6200 μSv each year through background radiation, which is radiation we encounter in daily life.³

The CBCT is an indispensable tool to each hygienist who has access to its use in daily practice. More importantly, its correct utilization yields significant gains to our patients including earlier detection of various types of lesions as well as better visualization and understanding of their own oral state of health, which may help them to accept the needed treatment to address periodontal disease and other conditions. As hygienists, our first commitment is to our patients − to educate them in such a way they can make informed decisions about their health and about the care they receive. Only then can we execute the level of therapy that excellent patient care dictates.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on pure education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Wilkins E. Clinical Practice of The Dental Hygienist. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:247.

- Li, G. Patient radiation dose and protection from cone-beam computed tomography. Imaging Sci Dent. 2013;43(2):63–69. doi:10.5624/isd.2013.43.2.63.

- Radiation Sources and Doses | US EPA. US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/radiation/radiation-sources-and-doses. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2019.