Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects communication and social interaction. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one in 36 children in the United States was diagnosed with ASD in 2020.1 That is an increase from one in 54 in 2016 (see Figure 1).

| Diagnostic Year | Prevalence

One in X children |

| 2020 | One in 36 |

| 2018 | One in 44 |

| 2016 | One in 54 |

| 2014 | One in 59 |

| 2012 | One in 69 |

| 2010 | One in 68 |

| 2008 | One in 88 |

| 2006 | One in 110 |

| 2004 | One in 125 |

| 2000 | One in 150 |

Figure 1 Prevalence of children diagnosed with ASD. Adapted from the CDC1

Approximately 2.1% of the adult population has been diagnosed with ASD.2 The increase in diagnoses is a result of clearer diagnostic criteria, and physicians are better equipped to identify and diagnose at an earlier age. Another reason for the increase is the advancement of medical intervention in preterm birth and the increased access to medical care at an early age.

Since dental care is an essential component of overall health, it is crucial to understand how ASD affects dental care both at home and in the dental office.

Dental Care at Home

Many individuals with ASD have difficulty with oral hygiene care at home, which can lead to dental caries and periodontal disease. A study published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders found that children with ASD had higher rates of dental caries compared to children without ASD.3 Additionally, individuals with ASD often have sensory issues and sensitivities, which can make tooth brushing and interdental cleaning uncomfortable or even painful.4

Several strategies can help individuals with ASD improve their oral hygiene at home. First, parents or caregivers can use visual aids, such as pictures or videos, to demonstrate proper brushing and interdental cleaning techniques. People with ASD often have unique learning styles and may benefit from visual cues to enhance their comprehension and retention of information. By providing visual demonstrations, individuals with ASD can more easily grasp the steps involved in oral care routines and improve their ability to perform these tasks independently.

Secondly, parents or caregivers can use sensory-friendly toothbrushes and toothpaste. Some manual toothbrushes have triple heads that allow for brushing the lingual, buccal, and occlusal aspects at the same time. By incorporating this approach, the duration of oral care can be minimized, as individuals with ASD often have limited tolerance for extended brushing. Consequently, simultaneously cleaning all three surfaces within the shorter timeframe that they are willing to endure will yield improved effectiveness and enhanced tolerance for their caregiver’s efforts. Furthermore, sensory-friendly toothpastes are typically mild in flavor.

Electric toothbrushes are a valuable tool, but they may not be a viable option due to the vibration. However, some individuals with ASD can be desensitized to this vibration over time. This can be done by first starting with brushing with no power. Next is turning it on in the mouth for just a few seconds without brushing. This is followed by slowly extending the time it is powered on while the toothbrush is in their mouth until, eventually, the person can have their teeth fully brushed with the power on. This is a lengthy process, but it is often very successful.

Some individuals with ASD may be sensitive to certain tastes or textures. For example, the texture of prophylaxis paste or strong mint flavoring can cause sensory overload. Therefore trying different types of toothpaste may be helpful to find one that is more tolerable. Additionally, some individuals may prefer a softer toothbrush or one with a larger handle for a better grip. Handle size can be increased by placing the toothbrush through a slit in a tennis ball or using thermoplastic beads that are able to be heated until they are clear and soft and then molded around the handle to fit the individual’s grip specifically.

Third, parents or caregivers can use positive reinforcement to encourage good oral hygiene habits. This can include providing rewards for brushing and interdental cleaning or using a schedule to track progress. Positive feedback in the form of verbal comments is a benefit to many individuals. Rewards such as stickers, small toys, or video game time are often key to success. These rewards will vary greatly from person to person and what meets their cognitive level as well as what speaks to their personality with positivity.

Dental Care in the Office

Receiving dental treatment can be a challenging experience for individuals with ASD. The dental office can be a sensory-rich environment with bright lights, loud noises, and unfamiliar smells. Additionally, individuals with ASD may have difficulty communicating their needs and some individuals with ASD may be nonverbal in their communication. Some may also have difficulty understanding instructions from the dental team.

According to a study published in Autism Research and Treatment, patients with ASD often felt that they were coerced into dental procedures they were not mentally ready for and typically reported they had dental experiences that were more painful. It also reported that these patients had more dental anxiety as well as different features of dental apprehension than neurotypical patients.5 This increased anxiety and previous negative experiences can make it difficult for patients with ASD to receive the dental care they need.

Several strategies can make dental visits more comfortable for patients with ASD. First, dental professionals can provide a sensory-friendly environment. This can include reducing sensory stimuli, such as turning down the lights or providing noise-canceling headphones. Reducing the light and noise can help reduce the possibility of overstimulation and lessen the patient’s anxiety. Additionally, dental professionals can provide weighted blankets or lap pads to provide a calming effect.

The dental x-ray (lead) apron can be used in place of a weighted blanket. However, this is sometimes met with reluctance because it signifies a dental object to the patient that may have the opposite effect and increase dental anxiety.

Secondly, dental professionals can use clear, simple, and brief language when communicating with patients with ASD. Speaking in a happy tone of voice and using positive wording will help to ease the patient’s fears. For example, telling them they are doing a great job or being a terrific patient, as well as saying that something may “feel a bit funny.”

Breaking down the dental visit into smaller steps can be helpful. An example for younger patients is, “We will start with pictures of your teeth. Next, we will count each tooth. After that, we will check each tooth to see if any sugar bugs are hiding. After that, we will tickle your teeth with a special toothbrush, and then we will paint on some special vitamins to help your teeth be strong.”

These smaller steps can help the patient understand what is happening currently and what is happening next. Using visual aids such as whiteboards with the steps written out that the patient can check off as each step is completed or picture boards to demonstrate these steps can also be useful. Showing patients with ASD the items that will be used ahead of time or just as they are about to be used ‒ such as the mirror, explorer, prophy angle, or curing light ‒ can help alleviate fears and increase compliance.

Third, dental professionals can provide desensitization opportunities to help patients with ASD become more comfortable with the dental office. This can involve allowing the patient to visit the office before their appointment. Scheduling a “get to know you” visit where no treatment is performed, only an introduction to the office and practitioner, or providing a “mock” dental exam to help the patient become familiar with the dental equipment and procedures may be helpful.

Lastly, it is important for dental professionals to be patient and understanding when working with patients with ASD. The practitioner needs to understand that any negative behavior, such as yelling, head banging, combativeness, or defiance, directly results from anxiety or overstimulation and is not typically in the patient’s control to change their behavior. Providing a calm and supportive environment can help reduce anxiety and fear and make the dental visit more comfortable for the patient.

Caregiver Tips

For caregivers of individuals with ASD, several tips can help make dental care at home and in the office easier. First, it is important to establish a routine for oral hygiene care at home. This can involve setting a regular time for brushing and interdental cleaning and using visual aids such as videos, pictures, or dolls that can have their teeth brushed to help the individual understand the steps involved.

Second, caregivers can work with the dental team to establish a dental care plan that meets the individual’s needs. This can involve discussing any sensory sensitivities or communication difficulties the individual may have. Bringing the patient’s personal weighted blanket or headphones from home can be comforting and familiar to them.

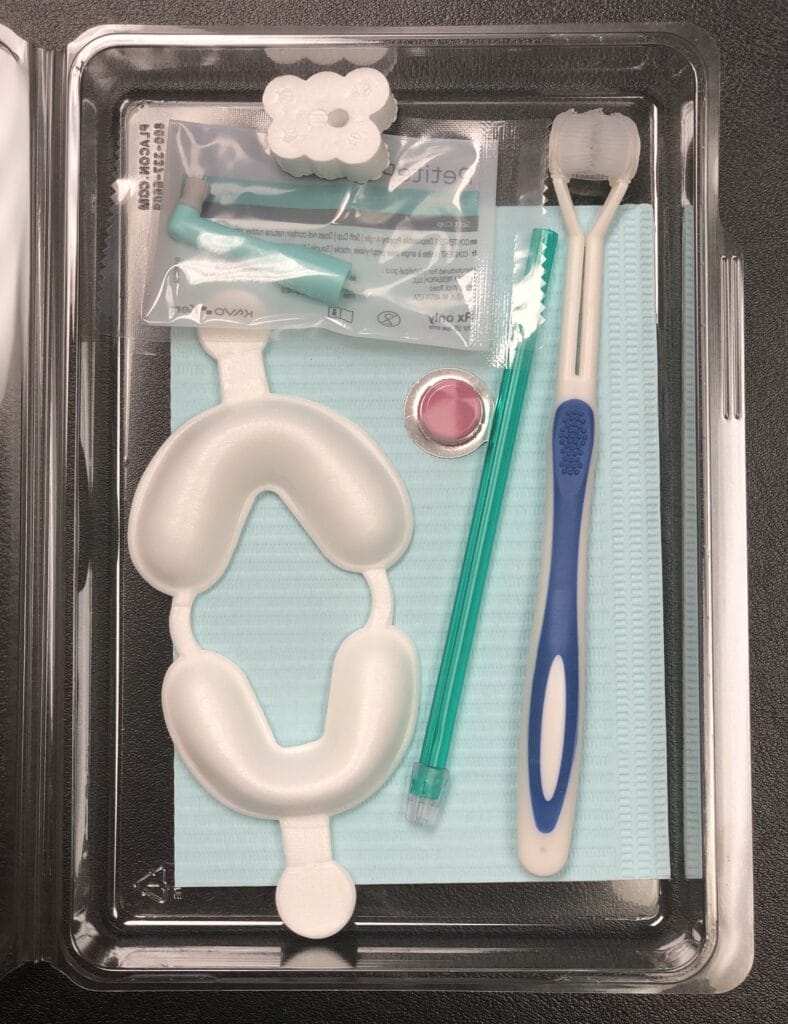

Third, caregivers can have a take-home kit allowing them to have practice dental visits in the comfort of their own homes (see Figure 2). These kits can include items such as prophy paste, patient napkin, disposable mouth mirror, prophy angle, and possibly a fluoride tray. The fluoride tray can be taken apart and used as a desensitizing tool in place of impression trays to practice or simulate taking impressions. These kits can help patients with ASD be more familiar with items they see in the dental office.

In Closing

Dental professionals and caregivers need to work closely together to make the dental visit less “scary” to the patient with ASD. Taking the time and working within each patient’s cognitive and anxiety levels will make for a more productive visit. Patience and perseverance with a positive approach are key to a successful visit. Doing these things will help to establish trust, lessen dental apprehension, and make dental visits less stressful. This, in turn, will aid in decreasing the barriers to dental care for patients with ASD.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on pure education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. (2023, April 4). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- Key Findings: CDC Releases First Estimates of the Number of Adults Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the United States. (2022, April 7). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/features/adults-living-with-autism-spectrum-disorder.html

- Burgette, J.M., Rezaie, A. (2020). Association between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Caregiver-Reported Dental Caries in Children. JDR Clinical & Translational Research; 5(3): 254-261. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31490715/

- Santosh, A., Kakade, A., Mali, S., et al. (2021). Oral Health Assessment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Special Schools. International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry; 14(4): 548-553. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1972

- Blomqvist, M., Dahllöf, G., Bejerot, S. (2014). Experiences of Dental Care and Dental Anxiety in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Research and Treatment; 2014; 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/238764