Health care in every area should be based on evidence. For years, the medical profession has evolved to provide better guidance and protocols to provide the standard of care across the board. Dentistry, though, has stayed stagnant for many years. To this day, dentistry is practiced on a spectrum, while other areas of health care are more calibrated with treatment protocols.

In dentistry, there are a few agreed-upon guidelines, but many decisions are based on personal experience and not science. In 2007, the American Dental Association (ADA) established the Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry and has been working to implement guidelines and evidence-based dental practice.

However, the ADA has struggled to gain a foothold among practicing dentists and dental hygienists. There are an estimated 202,304 dentists and 211,630 dental hygienists in the U.S., and we cannot all make decisions based on experience. Science must guide clinical decision-making. Otherwise, we are doing our patients a disservice.1-3

What is Evidence-based Dentistry?

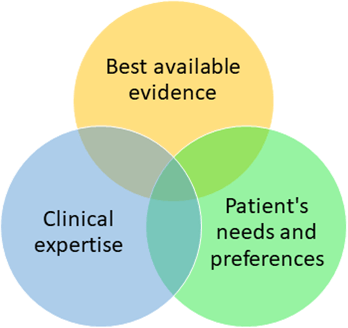

Evidence-based dentistry aims to integrate the best available evidence with clinical expertise and patient needs and preferences.4 The objective is to improve the quality of dental care our patients receive as well as calibrate the treatments for clearer guidance.4

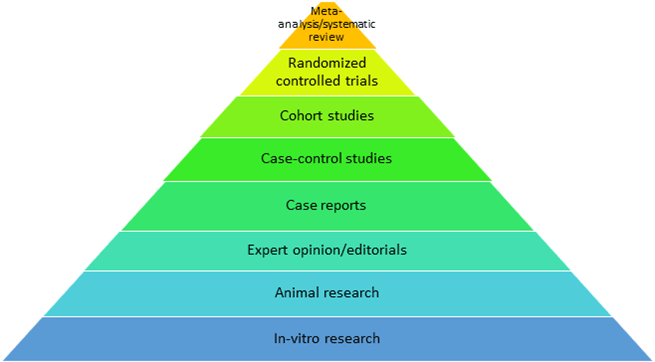

The best available evidence is grounded in research that provides evidence to support the treatment protocols used. The highest level of research evidence is systematic reviews and meta-analyses and/or randomized controlled trials.

When determining the level of evidence, there is a hierarchy of evidence that should be considered. The hierarchy of evidence is determined by the trustworthiness of the research and data. The higher level of evidence is the best available evidence, though, in different sections of the pyramid, both systematic reviews and meta-analysis, as well as randomized controlled trials, are considered the “gold standard” of evidence. Both are level one on the evidence hierarchy. This is the evidence that should be used in clinical practice.4

Nonrestorative Caries Management

Though efforts have been made to encourage minimally invasive approaches to dental caries through noninvasive, micro-invasive, clinical, and public health preventive services, the “drill and fill” approach is still predominant in many dental settings. The ADA has developed updated, evidence-based guidelines on the management and prevention of caries.5

An expert panel conducted a systematic review to create evidence-based clinical recommendations to arrest or reverse noncavitated and cavitated carious lesions using nonrestorative treatments for both children and adults.6

Recommendations for nonrestorative caries treatment coronal surface of primary teeth:6

- Occlusal noncavitated carious lesions: Sealants plus 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months) or sealants alone

- If this treatment is not feasible, the second-best treatment options are:

- 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months)

- 23% APF gel (application every 3-6 months)

- Resin infiltration plus 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months)

- 2% NaF mouth rinse (once per week)

- Occlusal cavitated lesions: 38% SDF solution

- Approximal noncavitated lesions: 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months) or resin infiltration alone

- Additional options include:

- Resin infiltration plus 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months)

- Sealants alone

- Approximal cavitated lesions: 38% SDF solution (annual application)

- Facial or lingual noncavitated lesions: 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months) or 1.23% APF gel (application every 3-6 months)

- Facial or lingual cavitated lesions: 38% SDF solution (annual application)

- Additional options include:

- If this treatment is not feasible, the second-best treatment options are:

Recommendations for nonrestorative caries treatment coronal surface of permanent teeth:6

- Occlusal noncavitated carious lesion: Sealants plus 5% NaF varnish or sealants alone

- If this treatment is not feasible, the second-best options are:

- 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months)

- 23% APF gel (application every 3-6 months)

- 2% NaF mouth rinse (once per week)

- Occlusal cavitated carious lesion: 38% SDF solution

- Approximal noncavitated lesions: 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months), or resin infiltration alone, or resin infiltration plus 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months), or sealants alone

- Approximal cavitated carious lesion: 38% SDF solution (annual application)

- Facial or lingual non-cavitated carious lesion: 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months) or 1.23% APF gel (application every 3-6 months)

- Facial or lingual cavitated carious lesion: 38% SDF solution (annual application)

- If this treatment is not feasible, the second-best options are:

Recommendations for nonrestorative caries treatment root surfaces of permanent teeth, both noncavitated and cavitated carious lesions:6

- 5,000 ppm fluoride (1.1% NaF) toothpaste or gel (at least once per day)

- If the above treatment is not feasible, choose one of the following:

- 5% NaF varnish (application every 3-6 months)

- 38% SDF solution plus potassium iodine (annual application)

- 38% SDF solution alone (annual application)

- 1% chlorhexidine/1% thymol varnish (application every 3-6 months)

- If the above treatment is not feasible, choose one of the following:

It is recommended that these areas be closely monitored to ensure treatment is successful. This can be done through radiographic evaluations indicating arrest or reversal over time and through observing signs of hardness. Clinicians should implement additional or alternate treatment options if there is any indication of progression.6

Of note, the expert panel specifically recommends against the use of 10% casein phosphuretted-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) to arrest or reverse noncavitated or cavitated carious lesions. The official statement from the panel states, “10% CPP-ACP should not be used as a substitute for fluoride products.”6

Caries Prevention

Dental hygienists are prevention specialists. Our role in health care is unique as our primary role is to prevent disease and not just treat it. Dental caries is one of the most common dental diseases among adults and children alike. Statistics from 2018 indicate 13.2% of children five to 19 years of age have untreated dental caries, while the incidence among the adult population ranges between 20.2% to 25.9%, with the age group 20 to 44 being the highest incidence.7

The ADA has provided multiple prevention strategies and guidelines to help guide clinicians in caries prevention.8 Fluoride toothpaste is a cost-effective prevention that should be implemented in children as soon as the first tooth erupts. Parents should help children brush until they have the dexterity to do it themselves effectively. I like to use the metric of when they can tie their own shoe, they can start attempting to brush on their own (with parents closely monitoring).9

The fluoride toothpaste recommendations for children are:9

- Children younger than three years: Use the amount of a grain of rice or no more than a smear and brush twice a day (morning and night)

- Children three to six years of age: Use a pea-sized amount and brush twice per day (morning and night)

It is important to use visual aids to help parents understand and visualize the amount of toothpaste that should be used for children and the proper techniques to help parents successfully brush their children’s teeth. There are a plethora of images online, as well as an image on the ADA website (Figure 1), that you can refer to when discussing how much toothpaste to use.9

Topical Fluoride Treatments

Professionally applied topical fluoride treatments are also recommended for patients with an increased risk of developing caries. The following table shows different options that are recommended for professionally applied topical fluoride. This can help when deciding which option is best for your patients.10

| Age Group or Dentition Affected | Professionally Applied Topical Fluoride Agent |

| Younger than six years | 2.26% fluoride varnish at least every three to six months |

| Six to 18 years | 2.26% fluoride varnish or 1.23% APF gel for four minutes at least every three to six months |

| Older than 18 years | 2.26% fluoride varnish or 1.23% APF gel for four minutes at least every three to six months |

| Adult root caries | 2.26% fluoride varnish or 1.23% APF gel for four minutes at least every three to six months |

Adapted from Weyant, R.J., et al.10

Additional information of note from the ADA guidelines:10

- 1% fluoride varnish, 1.23% APF foam, or prophylaxis paste are not recommended for preventing coronal caries in all age groups

- No prescription-strength topical fluoride agents except 2.26% fluoride varnish are recommended for children younger than six

- Prophylaxis prior to 1.23% APF gel application is not necessary for all age groups

A growing number of patients are leaning toward avoiding fluoride. Though fluoride is safe in the doses we use it in dentistry, chemophobia (the fear of chemicals) is growing with the dissemination of misinformation (inaccurate) and disinformation (deliberately misleading). Social media and the internet have allowed people to misrepresent toxicology in the sense that they don’t consider the dosage but simply make the blanket statement that a substance is “toxic.” This movement has created the need for alternatives to fluoride for caries prevention.11

I would like to add a caveat before moving forward with the expert panel recommendations. That caveat is that the expert panel clearly states, “nonfluoride preventive agents should be considered as adjunctive to a regular caries prevention program.” That means we should be recommending fluoride along with these nonfluoride options. These options do not replace fluoride as a caries prevention. Though some patients will still decline fluoride, it is imperative we explain that using nonfluoride adjuncts alone is not evidence-based for the prevention of caries.12

Nonfluoride caries prevention agents include:12

- Polyol (coronal caries)

- Patients five years and older can use sucrose-free polyol (xylitol or polyol combinations) chewing gum for 10 to 20 minutes after meals

- Patients five years and older can use xylitol-containing lozenges or hard candy that dissolves slowly in the mouth after meals (five to eight grams/day divided into two to three doses)

- Chlorohexidine (root caries)

- Apply 1:1 chlorhexidine/thymol varnish every three months

- Apply 0.5 to 1.0% chlorohexidine gel alone or in combination with fluoride is not recommended

- Using 0.12% chlorohexidine rinse alone or in combination with fluoride is not recommended

- Chlorohexidine (coronal caries)

- Applying 1:1 chlorohexidine/thymol varnish alone or in combination with fluoride is not recommended

- Applying 10 to 40% chlorohexidine varnish alone or in combination with fluoride is not recommended

- Applying 0.5 to 1.0% chlorohexidine gel alone or in combination with fluoride is not recommended

- Using 0.12% chlorohexidine rinse alone or in combination with fluoride is not recommended

In summation, the only evidence-based nonfluoride options for coronal caries prevention are polyols. The only evidence-based nonfluoride option for root caries is 1:1 chlorohexidine/thymol varnish.12

I see and hear a lot of talk about arginine and nano-hydroxyapatite. However, there is not enough evidence to support their use currently. If you are recommending either of these products as a replacement for fluoride, please advise your patients that it is not an evidence-based practice.12

Sealants

When I think of treatment options most left to personal experience, I think of sealants. Many dental professionals avoid placing them because they claim decay can develop under them and cause a bigger problem. However, the evidence is in stark contrast to these anecdotal experiences.13

If you have decided to omit sealants as an option for caries prevention, you are not practicing evidence-based dentistry. Furthermore, you are not providing your patients with all their options which takes away their autonomy, which is one of the pillars of the patient’s rights.14 The evidence regarding sealants shows a 76% reduction in caries, which is quite significant.

The expert panel recommendations for sealants are as follows:13

Sealant placement in permanent molars with both sound occlusal surfaces and noncavitated occlusal caries in children and adolescents

- Prioritize the use of sealants in permanent molars with both sound occlusal surfaces and noncavitated occlusal caries lesions over fluoride in children and adolescents

- No recommendation for one type of sealant over another – the panel was unable to determine superiority

Keep in mind that professional and home fluoride and pit and fissure sealants remain the primary choices for caries prevention.12 Any nonfluoride options should be used as an adjunct. If a decision must be made between using sealants versus fluoride for noncavitated and cavitated occlusal carious lesions, sealants are the first choice.13

Conclusion

Evidence-based practice is meant to protect the clinician from liability and provide patients with the best care and treatment options while calibrating the standard of care among health care professionals. Though clinicians have all had personal experiences that may counter some of the evidence, we must remember anecdotal evidence does not trump evidence supported by robust data. Correlation does not equal causation.

It is in the best interest of our patients to provide them with a standard of care that can be backed by evidence. This will also protect you as a health care professional in the event you find yourself involved in litigation. If you find you are not practicing evidence-based dentistry, I encourage you to shift the way you practice to encompass the evidence-based dentistry model.

Following the clinical practice guidelines makes decision-making less stressful, and the care provided from hygienist to hygienist remains the same. Patients are often thrown for a loop when two hygienists in the same dental office practice differently. There is a level of reassurance in knowing what to expect at dental appointments, which could also lead to the patient being less stressed and anxious. However, the biggest benefit, in my opinion, is that you can sleep at night knowing you provided your patients with the best care based on current evidence.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Nalliah, R. Trends in US Malpractice Payments in Dentistry Compared to Other Health Professions – Dentistry Payments Increase, Others Fall. Br Dent J. 2017; 222: 36-40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.34

- The Dentist Workforce. (2023). American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/dentist-workforce

- Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. (2023, May). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291292.htm

- Durr-E-Sadaf. How to Apply Evidence-based Principles in Clinical Dentistry. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2019; 2019(12): 131-136. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S189484

- Fontana, M., Pilcher, L., Tampi, M.P., et al. Caries Management for the Modern Age: Improving Practice One Guideline at a Time. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2018; 149(11): 935-937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.09.004

- Slayton, R L., Urquhart, O., Araujo, M.W.B., et al. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline on Nonrestorative Treatments for Carious Lesions: A Report from the American Dental Association. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2018; 149(10): 837-849.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002

- Oral and Dental Health. (2024, May 22). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/dental.htm

- Clinical Practice Guidelines and Dental Evidence. (n.d.). American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/en/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/evidence-based-dental-research

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Fluoride Toothpaste Use for Young Children. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2014; 145(2): 190-191. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.2013.47

- Weyant, R.J., Tracy, S.L., Anselmo, T.T., et al. Topical Fluoride for Caries Prevention: Executive Summary of the Updated Clinical Recommendations and Supporting Systematic Review. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2013; 144(11): 1279-1291. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057

- Siegrist, M., Bearth, A. Chemophobia in Europe and Reasons for Biased Risk Perceptions. Nature Chemistry. 2019; 11(12): 1071-1072. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0377-8

- Rethman, M.P., Beltrán-Aguilar, E.D., Billings, R.J., et al. Nonfluoride Caries-preventive Agents: Executive Summary of Evidence-based Clinical Recommendations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2011; 142(9): 1065-1071. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0329

- Wright, J.T., Crall, J.J., Fontana, M., et al. (2016). Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Pit-and-fissure Sealants: A Report of the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2016; 147(8): 672-682.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.06.001

- Olejarczyk, J.P., Young, M. (2024, May 6). Patient Rights And Ethics. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538279/