According to the Oral Cancer Foundation, one person in the United States dies every hour each day from oral cancer.1 Dental hygienists are often the first clinicians to detect these cancers in our patient’s mouths, but the identification of suspicious lesions in the oral cavity can be tricky. However, the more familiar we become with identifying suspicious lesions, the better outcomes we will hopefully yield for our patients.

Many lesions commonly found in the oral cavity are benign. However, others that we will see at some point during our careers are precancerous and even cancerous. This is why it is so imperative for us to be vigilant about recognizing suspicious lesions and educating our patients about them.

I realize it can be difficult to point things out to patients that may be worrisome. We never know how they’re going to react. Will they be angry? Scared? Confrontational? Appreciative? As health care providers, we have an obligation to our patients. Whether I suspect a lesion is malignant or not, I educate the patient about the importance of a biopsy.

Early Detection and Diagnosis

The Oral Cancer Foundation states that if cancers are caught early, patients may suffer fewer “treatment disfigurations” compared to their counterparts whose cancers are detected at a later stage.1 Similar to different malignancies found in other areas of the body, a patient’s prognosis can depend upon how early it is detected.1,2

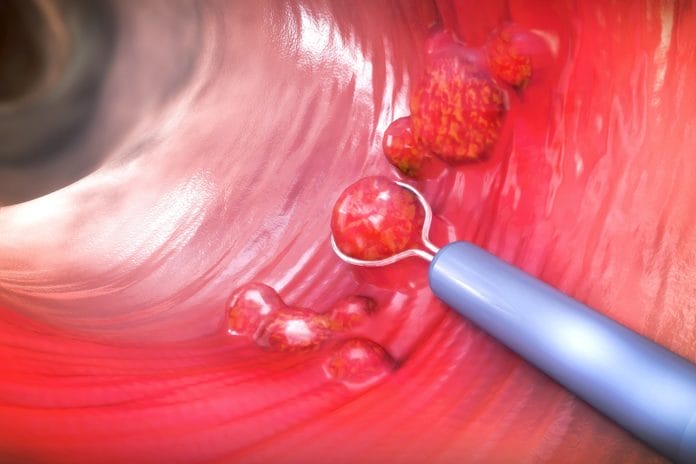

While we know there are adjunct tools to help identify suspicious lesions, the gold standard for definitively diagnosing a lesion for malignancy is a scalpel biopsy.2,3 The American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs and the Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry “does not recommend autofluorescence, tissue reflectance, or vital staining adjuncts for the evaluation of PMDs [potentially malignant disorders] among adult patients with clinically evident, seemingly innocuous, or suspicious lesions.”2

One study comparing two light-based screening adjuncts stated, “Clinicians and patients could have a false sense of security” because “potentially large numbers of precancerous lesions will be missed by both devices.”4

One doctor who I work with compares an oral biopsy to going to a dermatologist. If a dermatologist sees a suspicious mole or another odd skin lesion anywhere on the body, they remove it and look at it under the microscope. The same should apply to dental professionals.

Viewing Biopsy Histology Reports

I have the privilege to work in a specialty practice where our doctors perform most of their biopsies, so I am able to see the histology reports. This has helped me immensely in becoming more knowledgeable and comfortable with oral pathology. If you work in an office where biopsies are not routinely performed, requesting a copy of the report for your patients may be helpful so that you can become familiar with their condition.

During my career, I have found lesions in a large number of patients. The majority of the biopsy reports I have seen come back noting nothing of concern. However, sometimes, the results have come back as dysplasia, which means it has the potential to turn cancerous. There have been a few instances of different oral cancers as well. Benign lesions like trauma will typically have healed within two weeks; if a lesion has been present longer than this and is suspicious, a biopsy is warranted.1,2,4

The biopsy results also help determine how often a patient needs to be seen for a follow-up. If a patient is currently on a six-month recall, they may need to be seen more frequently for an intraoral exam to ensure nothing has changed or progressed. It also helps determine if the patient will need to be seen by another specialist, such as an oral pathologist.

Patient Education and Documentation

I have always practiced clinical hygiene with loupes and a headlight, and I feel they have been instrumental in being able to spot suspicious lesions. Intraoral cameras are also an invaluable tool for these lesions − not only to provide documentation but also for patient education.

Sometimes, it’s difficult for patients to understand what we’re describing. Just as you show a patient decay on a radiograph, having a photo of a suspicious lesion is extremely helpful. It’s been my experience that patients can better grasp the seriousness of the situation and appreciate the need for a biopsy once they’ve seen a picture of the lesion.

A detailed description of the lesion should be included in a patient’s chart. The description of a lesion should include:

- Location: Inferior, superior, lateral, medial, etc., to landmarks such as the closest anatomical structure or tooth number

- Distribution: Localized or generalized (diffuse), single or multiple (if multiple, coalescing, or distinct and separate)

- Margins: Well-defined (circumscribed) or ill-defined

- Size and shape: Measurements of length, width, and height

- Color: Pigmented, erythematic, white, yellow, or the same color as surrounding tissue

- Consistency: Soft, indurated, fluctuant, purulent

- Surface texture: Papillary, corrugated, fissured, crusted, pseudomembranous

- History: How long the lesion has been present, noted changes, recurrence, past lesions, relevant health history information, familial history, and any other details related to the lesion, such as if it’s painful or other altered sensations

In Closing

Dental hygienists play a crucial role in detecting suspicious lesions, whether benign, precancerous, cancerous, or the first sign of a systemic condition.

Take pemphigus, for example, which is a disorder that causes blisters and erosions of the skin and mucous membranes, which can be potentially life-threatening. One study concluded that 60% of patients with pemphigus vulgaris develop oral lesions first before anywhere else in the body. The study concluded, “Timely recognition and therapy of oral lesion is critical as it may prevent skin involvement.”5

We may be the first person to detect something like this in our patients, and early diagnosis can lead to better patient outcomes.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Oral Cancer Facts: Rates of Occurrence in the United States. (n.d.). Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/facts/

- Lingen, M.W., Abt, E., Agrawal, N., et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation of Potentially Malignant Disorders in the Oral Cavity. 2017; 148(10): 712-727. https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(17)30701-8/fulltext

- Epstein, J.B., Silverman, S., Epstein, J.D., et al. Analysis of Oral Lesion Biopsies Identified and Evaluated by Visual Examination, Chemiluminescence, and Toluidine Blue. Oral Oncology. 2008; 44(6): 538-544. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1368837507002072

- Mehrotra, R., Singh, M., Thomas, S., et al. A Cross-Sectional Study Evaluating Chemiluminescence and Autofluorescence in the Detection of Clinically Innocuous Precancerous and Cancerous Oral Lesions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010; 141(2): 151-156. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20123872/

- Arpita, R., Monica, A., Venkatesh, N., et al. Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris: Case Report. Ethiopian Journal of Health Science. 2015; 25(4): 367-372. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4762976/