Barodontalgia, also known as “tooth squeeze,” is pain in the tooth region after a pressure change. The name reflects the condition – “baro” means pressure, and “odontalgia” means tooth pain. It is an acute toothache with high sensitivity when a sudden change in environmental pressure occurs.1

Another condition is dental barotrauma that happens when changes in barometric pressure generate damage to the dentition. Changes in barometric pressure may induce fractures of dental hard tissue or restorations. This was first recognized as a condition with military pilots in World War II, originally called aerodontalgia. Then later, this tooth pain was detected in scuba divers to give it the term barodontalgia.2

Dental professionals play a role in relieving the condition by checking dental restorations, particularly those present in members of specific occupations.

Barodontalgia

Barodontalgia is most common in underwater divers and airline pilots, where they experience atmospheric pressure changes quite often. It may also happen in other activities with pressure changes, such as in skydivers, high-altitude mountain climbers, submariners, and personnel who work in medical pressure chambers. Height and depth changes cause barodontalgia, with sensations and results being the same with either height or depth.2

Boyle’s law (the volume of gas at constant temperature varies inversely with the surrounding pressure) is a factor in barodontalgia. It’s basically when there’s more pressure inside the tooth than outside the tooth. Barodontalgia is any gas trapped in a space inside a tooth and feeling like it’s being squeezed to cause pain.

Gas gets trapped in a tooth through different avenues. Trapped gas in a dead nerve space diffuses more slowly from a lack of vasculature. When gas is trapped in the periodontal ligament, it diffuses more rapidly because of the hardy blood supply. Within a tooth fracture of either a vital or nonvital nerve, trapped gas could cause pain for a variable amount of time. Leaky fillings or fractures may act as a one-way channel for gas that gets into a tooth easier than it is released from a tooth, causing intense pain.3

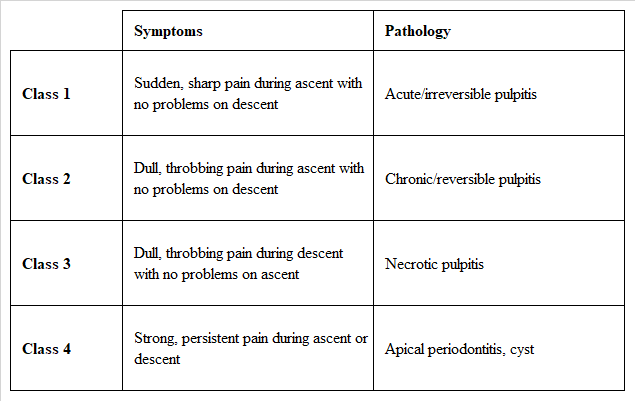

Barodontalgia is a symptom rather than a pathologic condition itself. It’s usually a flare-up of preexisting oral conditions to create an occurrence pressure, and pathology in oral tissues or sinuses must be present4 (see Figure 1).

(Ascent is arriving at a higher level. Descent is the act of moving downward, dropping, or falling.)

Dental Barotrauma

Dental barotrauma is pressure-induced damage that occurs at both high and low pressures. It occurs with preexisting pathology in the oral cavity. The more treatment a tooth has undergone in its lifetime, the more susceptible it is for problems to occur under barometric change.3

These preexisting dental conditions are a cracked tooth, dental caries, defective tooth restorations, pulpitis, pulp necrosis, apical periodontitis, periodontal pocketing, and an impacted tooth. If a tooth has been injured or bacteria is trapped within the chamber, pressure begins to build and cause pain. If the tooth is already compromised and then adding atmospheric pressure, it can be excruciating. A crack in a tooth allows air to enter, causing it to expand or contract with changes in pressure3

Barosinusitis

Barosinusitis, also called sinus squeeze or sinus barotrauma. It’s a painful acute or chronic inflammation of one or more paranasal sinuses produced by the development of a pressure difference (usually negative) between the air in the sinus cavity and that of the surrounding atmosphere. There may be bleeding of the membranes of the paranasal sinus cavities.

Pressure differences occur in the body when a gas-filled cavity is unable to relate with the exterior of the body, causing pressure to be unequal. When the internal and external pressure difference happens, it can promote pain, oedema, or vascular gas embolism. This type of pain occurs in the lungs, middle ear, or maxillary sinuses.1

Barosinusitis is a common source of dental pain from barometric pressure caused in the maxillary sinuses. Acute or chronic sinusitis is usually present beforehand.5 Stimulation of nociceptors in the maxillary sinuses may act as referred pain to the teeth while there may not be any pathology.3

While barosinusitis is sinus related and occurs on descent, barodontalgia is tooth-related and occurs on ascent.5

Scuba Divers

In scuba diving, barodontalgia may arise during descent or ascent. Scuba divers tend to feel it during the descent of the dive and generally at 10 to 25 meters when the ambient pressures are 0.75 and 1 atmosphere. Barotrauma can happen on descent or ascent.

Barotrauma of descent is when an enclosed gas-filled space fails to adjust its internal pressure with the external pressure resulting in damaged tissue.

One of the biggest dental complaints experienced by divers is the feel of dental squeeze. This arises from exposed dentinal tubules or pulpal tissue. During the descent, air is forced into the pulp from the increased pressure of the inspired air. The pain felt is in correlation to the diver’s depth and improves during the ascent when pressure is relieved. This compressed air reaches the dental tubules through caries along the margins of restorations or around leaking restorations.

Pulpitis from recent dental treatment could be another cause of barotrauma.2,5 Dental treatment in general causes to some degree inflammation with subsequent swelling in the pulp resulting in sensitivity for a few days after treatment. When pressure is applied on inflamed tissue, gases produced from the inflammation process and compressed and increased pressure in the pulp cavity produce pain.

After a tooth extraction or minor oral surgery, the inflammation should subside before diving as pain and bleeding may be induced by increased pressure. Similarly, after a new restoration, it should be advised not to dive, especially performing a deep dive.6

Barotrauma of ascent is caused by compressed air trapped in an enclosed space and then expands during the ascent. This injury happens more so in teeth with incomplete root canal treatments or neglected restorations.

During descent, compressed air slowly enters the teeth that have a poor physical seal of the tooth to the restoration but cannot escape quickly enough during ascent. As the diver’s depth decreases, pressure builds up within the tooth due to expansion of the trapped air leading to severe pain and sometimes even fractures. In more severe cases, odontecrexis transpires which is when the trapped air in a tooth rapidly expands, causing a tooth to explode.6

Aviation

During high altitudes when flying, the outside pressure decreases as the volume of gases increase in a compromised tooth. This affects the tooth chamber and canals when gases cannot expand and contract to adjust pressure internally to equalize externally.6 The teeth affected by barodontalgia are already compromised with faulty restorations, recurrent decay, fractures, or air bubbles that may happen during the restorative process. A crown may even be dislodged if the cement layer under the crowns has micro air bubbles.4

At great heights, whether in pressurized or nonpressurized cabins, barodontalgia may occur in a range of altitudes from 5,000 to 35,000 feet, although it is more common between 9,000 to 27,000 feet.6 Pilots may not report any tooth pain as barodontalgia can be so painful that it may cause grounding of a pilot.2

Valsalva Maneuver

Valsalva maneuver is a technique performed to relieve internal pressure − the act of attempting to exhale with the nostrils and mouth are closed. This maneuver is used to clear the pressure changes in the sinuses or ears. This increases pressure in the middle ear and the chest and is used as a means of equalizing pressure.

It’s the simple method of holding the nose and gently blowing with a closed mouth. This process forces air into the eustachian tubes to equalize the space behind the eardrum and forces air simultaneously into the sinus cavity to equalize these spaces.

This technique is not only performed with scuba divers or flying on an airplane, but oddly enough with hiccups and tachycardia.7

Prevention and Diagnosis

The key to avoiding barodontalgia or barotrauma is good oral health with regular dental checkups to ensure healthy restorations and crowns. Making certain restorations are solid with a tight seal free of air spaces and not chipped or broken. Since the pain only happens at atmospheric pressure, it’s challenging to mimic the pain during an exam to determine which tooth it may be. If knowing the patient is involved with atmospheric pressure changes, awareness of exposed dentin, caries, fractured cusps, fillings, and periapical pathologies is crucial.

Many times, people won’t notice a compromised tooth until after pressure changes were experienced to rile up the tooth.5 For these high-risk patients who fly or scuba dive often, periodic dental examinations should include periapical radiographs, panoramic radiographs every three to five years, and vitality tests. The exam should offer detailed attention to periapical pathosis, faulty restorations, secondary caries, and teeth attrition.

Most cases of barodontalgia are from faulty dental restorations or decay extended into the dentin. Other causes are pulpitis with periapical inflammation or after a recent dental restoration has been placed. The movement of fluids from dentin carious is considered to be the cause of pulpitis. Pressure changes have also been the cause of fractures of teeth that have dental restorations. The gas trapped between the restoration and tooth causes pain and causes fractures in the tooth.1

Certain filling materials are more efficient than others in improving barodontalgia pain. A resin cement group, zinc phosphate groups, and glass ionomers were tested under differing pressure. The resin cement groups held up the best with the best retention and less microleakage in comparison with the other materials, possibly due to its flexibility.4,5

A zinc oxide eugenol base has been proven to prevent barodontalgia when reversible pulpitis is diagnosed. When an exposed pulp is present, choosing endodontic treatment is indicated over pulpectomy and capping.5

If a patient is a known frequent flier, has a career in aviation, or is a scuba diver, it may better to be proactive in treating older restorations and decay rather than watching or monitoring a tooth. Being dutiful with treatment with these high-risk barodontalgia patients will lower the chance of feeling pain and improve their quality of life during their chosen activities.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Stoetzer, M., Kuehlhorn, C., Ruecker, M., et al. Pathophysiology of Barodontalgia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Reports in Dentistry. 2012; 2012: Article ID 453415. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/453415.

- Barodontalgia -Toothache Triggered by Hypobaric and Hyperbaric Conditions. (2014, January 18). Worldwide Military-Medicine. Retrieved from https://military-medicine.com/article/3102-barodontalgia-toothache-triggered-by-hypobaric-hyperbaric-conditions.html.

- Stein, L. (2000, January/February). Dental Distress. Alert Diver: The Magazine of Divers and Alert Network. Retrieved from https://www.diversalertnetwork.org/membership/alert-diver/articles/public/AlertDiver_JF00_45-48.PDF.

- Zadik, Y. Aviation Dentistry: Current Concepts and Practice. Br Dent J. 2009; 206: 11–16. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.1121.

- Robichaud, R., McNally, M.E. Barodontalgia as a Different Diagnosis: Symptoms and Findings. J Can Dent Assoc. 2005; 71(1): 39-42.

- Kini, P.V., Jathanna, V., Rakesh, J., et al. Barodontalgia: Etiology, Features and Prevention Open Journal of Dentistry and Oral Medicine. 2015; 3(2): 35-38. DOI: 10.13189/ojdom.2015.030201 Retrieved from http://www.hrpub.org/download/20150510/OJDOM1-18003673.pdf.

- Fogoros, R.N. (2019, November 28). Valsalva Maneuver Works and the Vagus Nerve. Very Well Health. Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/valsalva-maneuver-1746152.