Burning mouth syndrome is a benign condition affecting about 2% of the population.1 Women are about seven times more susceptible to this condition than men. Within women, pre/peri-menopausal women are at higher risk. Burning mouth syndrome is more common in adults over 60 years of age.2

Burning mouth syndrome can be chronic or periodic and last from days to weeks to months or even years. It may be mild, moderate, or severe. Symptoms may be constant throughout the day or intermittent and can present themselves as minimal burning upon wakening and progress during the day to worsen by evening.3

Patients report burning mouth syndrome feels like a hot, tingling, numb, tender, or burning sensation. It may equally feel scalding, similar to the initial feeling when the mouth is burnt with hot food or liquid. The discomfort can be irritating and painful.3,4

Although burning mouth syndrome symptoms arise anywhere in the mouth, these sensations are most commonly experienced on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, followed by the tongue’s dorsal surface, lateral borders of the tongue, anterior hard palate, and labial mucosa.4

In addition to burning and other sensations, an estimated 70% of individuals with burning mouth syndrome experience taste disturbances. These taste disturbances are described as bitter, metallic, or sometimes both. Around 66% of individuals experience xerostomia as well.4

Etiology

While there are no known causes, burning mouth syndrome is believed to be a form of neuropathic pain. The nerve fibers in the mouth function abnormally to transmit pain, even though there is no pain stimulus. It is suggested that the nerves in the mouth responsible for feeling pain are easily stimulated and excited.1

There are two classifications of burning mouth syndrome: primary and secondary.2

Primary

Primary burning mouth syndrome, which is also called idiopathic burning mouth syndrome, has no identifiable cause; it is a disease of exclusion. Tests can be run to exclude other causes, such as underlying medical conditions. In the absence of any underlying medical conditions, a diagnosis of primary burning mouth syndrome may be appropriate.

Experts believe primary burning mouth syndrome is due to nerve damage that controls pain and taste. Though there is no definitive causal factor, it has been observed through immunohistochemical and microscopic tests there is “axonal degeneration of epithelial and subpapillary nerve fibers in the affected epithelium of the oral mucosa.”4

When patients present with symptoms of burning mouth syndrome, the best practice is to refer them to their primary care physician for tests to rule out underlying medical conditions that may be a contributing factor. If it is determined that there are no underlying conditions, referrals to specialists such as oral surgeons, oral medicine, and/or oral pathologist may help with the diagnosis.2,3

Primary burning mouth syndrome is difficult to diagnose. Most individuals present with little to no oral health issues that would indicate a problem.3 Tests are often done to identify or eliminate contributing factors, including the following:

- Neurological imaging to rule out pathology or degenerative disorders

- Oral cultures to check for bacterial, viral, and fungal infections

- Lab work to eliminate nutritional, autoimmune, or hormonal deficiencies

- Patch test for allergies

- Check for gastric reflux

- Treat psychological stressors and well being

- Check saliva flow4

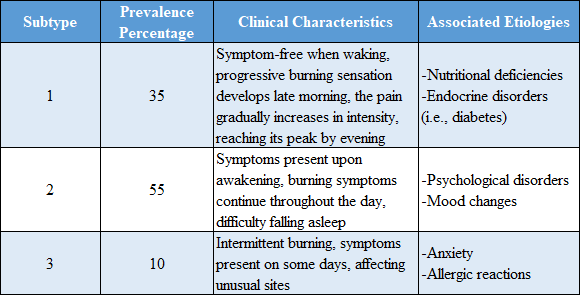

Based on the level of pathology involved, primary burning mouth syndrome has also been broken down further into three subtypes or subgroups (see Figure 1). “The first subgroup is characterized by peripheral small diameter fiber neuropathy of oral mucosa. The second subgroup consists of pathology involving the lingual, mandibular or trigeminal system, and the third subgroup, labeled as having central pain, may involve the hypofunction of dopaminergic neurons in the basal ganglia.”2 Some individuals will overlap in these subtypes.2

Secondary

An underlying medical issue causes secondary burning mouth syndrome.3 The medical conditions associated with burning mouth syndrome can be local, systemic, or psychological. The etiology can be and most often is multifactorial.4

Common causes of secondary burning mouth syndrome include:

- Bruxism and clenching

- Depression

- Hormonal changes, including diabetes and thyroid issues

- Oral allergies

- Xerostomia due to systemic disease, medications, and/or radiation therapy

- Medications, especially medications to treat hypertension

- Nutritional deficiencies, low levels of B vitamins and/or iron

- Oral infections such as candida infections, lichen planus, and stomatitis

- Acid reflux3

Etiology Theories

Though the etiology of burning mouth syndrome is currently unknown, there are multiple theories about the mechanism that elicits the burning sensation and taste disturbance.4

The following are a few of the theories of the etiology of burning mouth syndrome:

- Abnormal interactions between the sensory functions of the facial and trigeminal nerves

- Sensory dysfunction with small and/or large fiber neuropathy

- Disturbances in the autonomic innervation and oral blood flow

- Chronic anxiety and stress, which can alter steroid levels in skin and oral mucosa4

According to the theory regarding the abnormal interactions between sensory functions of the facial and trigeminal nerve, this theory postulates that “supertasters,” who are mainly female, are at an increased risk of developing a burning sensation. The researchers state this idea is based on the high density of fungiform papilla present on the anterior aspect of the tongue. Interestingly, this fits the epidemiology as most individuals that suffer from burning mouth syndrome are female.4

There are multiple conditions to consider when making a differential diagnosis. However, these are not etiologic factors and should not be determined as such. For instance, the list of conditions associated with secondary burning mouth syndrome is not the etiologic factor(s); rather, they are contributing factors.4

Diagnosis

As mentioned, the diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome can be tricky and difficult. A thorough and complete medical history is needed to determine a diagnosis, and medical histories should be updated regularly. If a patient presents with symptoms associated with burning mouth syndrome, an updated medical history is warranted, even if it was recently updated.4

A thorough evaluation of the oral mucosa is necessary to rule out local irritants and systemic causes. Objective measurements of salivary flow rates and inquiring about taste dysfunction, such as the presence of bitter or metallic tastes, are necessary to make a differential diagnosis.4

Though hygienists are not therapists, a simple question or discussion about the patient’s previous or current psychosocial stressors and psychological well-being can provide valuable information. Conversations about psychological well-being can be difficult, but they are necessary and may require a referral to a qualified mental health practitioner for a full evaluation if the patient indicates severe distress.4

Other valuable information can be gathered through a simple interview process by asking the appropriate open-ended questions such as:

- When did these symptoms first occur?

- Was there anything that caused the onset that you can pinpoint?

- How long does it last?

- How would you rate the pain level on a scale of 1-10, with 10 being the worst pain?

- How often does it occur?

- Where do you feel the pain/discomfort?

- Does anything make it feel better?

- Does anything make it feel worse?5

The answers to these questions may not directly diagnose burning mouth syndrome, but they may differentiate it from other orofacial pain disorders.4

Treatment

Since there is no cure, managing the symptoms is the goal. Some medications used to treat anxiety, depression, and other neurological disorders at low doses help reduce nerve fiber activity. Certain medications that may help are clonazepam, SSRIs, amitriptyline, nortriptyline doxepin, and gabapentin. These medications may also help with sleep if this condition is keeping a patient awake at night.4

Over-the-counter medications that may be helpful are alpha lipoic, which is neuroprotective, and topical capsaicin, used as a desensitizing agent. If indicated, supplemental vitamins such as vitamin B complex, vitamin B12, folic acid, iron, and zinc may alleviate oral symptoms. It is important to have the patient discuss these options with their primary care physician before taking any supplements to ensure safety and compatibility with any other medications the patient may be taking.4

In some cases, managing symptoms of burning mouth syndrome for acute pain relief can be achieved. Recommendations should be tailored to each patient as the symptoms often vary. Advise the patient that trying multiple recommendations may be necessary to determine which works best for them.2

Recommendations for relief of discomfort from burning mouth syndrome include:

- Suck on small ice chips to help relieve the burning sensation

- Drink or sip on cold liquids

- Avoid or limit acidic, spicy, or hot foods or drinks

- Avoid any food or drink that personally triggers the symptoms

- Abstain from smoking and alcohol

- Use oral hygiene products for sensitive mouths; try baking soda and water concoctions to help soothe and neutralize the mouth2

In Closing

Burning mouth syndrome is an aggravating condition. Though it may not always be evident through clinical signs, the patient’s symptoms can help guide a diagnosis. When in doubt, always refer the patient for further tests with their primary care physician. This may be the only way to come to a definitive diagnosis, as burning mouth syndrome is often a diagnosis of exclusion. Though frustrating for patients and clinicians, obtaining a diagnosis is the first step in managing the patient’s symptoms and improving their quality of life.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on pure education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

See Also: Burning Mouth Syndrome: The Dental Hygienist’s Role in Assessment and Treatment

See Also: QUIZ: Test Your Burning Mouth Syndrome Knowledge

References

- Treister, N., Woo, S.B. (2015, January 22). Burning Mouth Syndrome. The American Academy of Oral Medicine. https://maaom.memberclicks.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=81:burning-mouth-syndrome&catid=22:patient-condition-information&Itemid=120

- Higuera, V. (2017, May 23). What is Burning Mouth Syndrome? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/burning-mouth-syndrome#treatment

- Burning Mouth Syndrome. (2022, September). NIH: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/burning-mouth/more-info

- Aravindhan, R., Vidyalakshmi, S., Kumar, M.S., et al. Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Review on its Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach.Journal of Pharmacy & BioAllied Sciences. 2014;6(Suppl 1): S21-S25. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.137255

- Gillam, D.G., Yusuf, H. Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice. Dentistry Journal. 2019; 7(2): 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7020051