Worldwide access to evidence-based clinical decision making must coexist with respect for individual decision making shaped by local culture and circumstances. This is the balance between globalizing the evidence and localizing the decisions that will improve delivery of healthcare worldwide.

-John Eisenberg

Abstract:

Purpose: This literature review demonstrates the importance for medical professionals to broaden their knowledge of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and the growing need for more evidence-based research, collaboration among health professionals, as well as the implantation of CAM education in all curriculums relating to healthcare.

Methods:

17 articles were used from searching the UBC library databases only including published, peer-reviewed, year of publication from 2000-present, and using the following key terms:

dental – professional – alternative – holistic – complimentary – medicine – research – study – herbal – Ayurveda – oral health – CAM – disease – students

Results:

Whether medical professionals felt positively (the majority) or negatively towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use, they perceived the absence of a strong evidence base and their lack of knowledge was not sufficient to make an informed judgment for their patients. Further research is needed for all patient populations to provide medical professionals with a greater understanding of their use of CAM to serve their patients’ needs within the current health system, as well as to understand the pattern of CAM use among patients and the general public.

Conclusion:

The emergence of CAM in our healthcare environment requires more information and education be provided to all medical professionals about CAM. Healthcare providers should be knowledgeable, as well as sensitive, to the different decision-making paths of their patients and be sensitive to the patient’s desire and belief system without judgment.

Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been defined as, “diagnosis, treatment, and/or prevention which complements mainstream medicine by contributing to a common whole, satisfying a demand not met by orthodoxy, or diversifying the conceptual framework of medicine.” (1) CAM represents a group of diverse medical and healthcare practices, products, and systems that may not be considered to be part of traditional, western medicine. More specifically, complementary medicine is used together with Western medicine, while alternative medicine is used in place of it. (2) The following methods are just some examples of CAM used today: acupuncture/acupressure, Alexander technique, animal therapy, aromatherapy, autogenic training, Ayurveda, (Bach) flower remedies, biofeedback, bio-electromagnetic therapy, essential oils, chelation therapy, chiropractic, Feldenkrais, herbal medicine, homeopathy, hypnotherapy, imagery, kinesiology, massage of any form, meditation, music therapy, naturopathy, neural therapy, osteopathy, qi gong, reflexology, relaxation therapy, shiatsu, spiritual healing, static magnets, tai chi, and yoga. (1)

As the public demand for CAM grows strong, medical professionals must be aware of what their patients’ beliefs, values, experiences, and opinions are towards the use of CAM to provide optimal care for clients. Knowledge of the characteristics of dental patients who use CAM is only a first step in developing a broader understanding how these and associated beliefs may affect treatment planning, public health programs, as well as oral health in general. Surveys indicate medical professionals and students are increasingly interested in CAM, yet a lack of knowledge is one of the greatest barriers to its appropriate use in the clinical setting. (3)

This literature review demonstrates the importance for medical professionals to broaden their knowledge of CAM and the growing need for more evidence-based research, collaboration among health professionals, as well as the implantation of CAM education in all curriculums relating to healthcare. This topic grows in significance alongside the growing population of those choosing alternative therapy over conventional approaches to their healthcare.

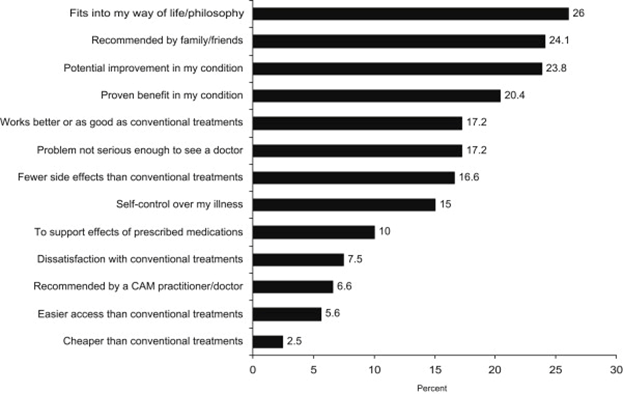

Why Are So Many Patients Using CAM? Will CAM Replace Conventional Medicine?

Patients are using CAM therapies for a variety of reasons, including the notion that basic health practices, such as good nutrition, exercise, and stress management, are the foundation for healing; that their bodies have the ability to heal themselves; and that they are responsible for their own healing and making choices regarding treatment options that promote holistic health and wellness and prevention of disease. (2) Nonetheless, The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) found that most people use CAM along with Western, or conventional, medicine rather than in place of it. (2) According to the NCCAM, most people use CAM because it would improve health when used in combination with conventional medical treatments, half of the people interviewed thought CAM would be interesting to try, and some felt conventional medical treatments would not help. (2)

Trends in Use: Is CAM Use Just a Fad?

The aim of the study by Kessler et al. was to present data on time trends in CAM therapy use in the United States over the past half-century. (4) A 1997–1998 national telephone survey of 2055 respondents, 18 years of age and older, among the 48 contiguous U.S. states, provided information on current use, lifetime use, and age at first use for 20 CAM therapies, in a retrospective self-reports of age at first use, for each of the therapies. (4) Previously reported analyses of this data showed more than one-third of the U.S. population was currently using CAM therapy in the year of the interview. Of respondents who used a CAM therapy, nearly half continued to use many years later, and a wide range of individual CAM therapies increased in use over time. (4) This growing trend demonstrates a continuing interest in and demand for CAM therapies that will undoubtedly affect healthcare delivery for some time to come.

As there have been several other community surveys done over the past decade confirming the evidence that a growing population uses CAM therapies, many managed care organizations responded to this trend by now providing insurance coverage for some CAM therapies. (4) Furthermore, most U.S. medical schools have begun offering courses on CAM therapies. (4) These responses again imply that CAM therapies are a force to be reckoned with for the foreseeable future.

Researchers guess that CAM therapies were used by a fairly small population until the 1970s, at which time the ideology associated with the youth counterculture led to a rapid and widespread use which has persisted to this day. (4) It goes without saying, the population of individuals using CAM therapies will increase as insurance coverage for the treatments expand. The trend of increased CAM therapy use across all cohorts since 1950, coupled with the high rate of persistence of use throughout one’s lifetime, suggests a continuing increased demand for CAM therapies that will affect all facets of healthcare delivery well over the next 25 years. (4)

The study by Kadam et al. was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of an Ayurvedic herbal tooth powder in the control of plaque the reduction of gingival inflammation in patients with moderate gingivitis. (5) Thirty subjects were randomly assigned to either the test or positive control group that used conventional toothpaste. (5) There was a significant reduction between scores of gingival index on day 1 and day 15 in both the groups, with no significant difference between the two groups at the end of treatment period. Thus a polyherbal combination of herbs mentioned in Ayurveda for oral hygiene has a potential for management of gingivitis. (5) This study showed that CAM therapies have the potential to be just as effective as conventional therapies and they recognized the expanding enthusiasm amongst patients who will increasingly be seeking information about CAM from health service providers.

Opposing Arguments

Arianne Shahvisi is a lecturer in Ethics and Medical Humanities at Brighton and Sussex Medical School. She explores issues of informed consent relating to CAM use and recommendations. Generally, informed consent is based on the notion it promotes patient autonomy. To be effective in this context, Shahvisi argues that truly informed consent entails the patient sufficiently understanding how the treatment works and why it (and not another treatment) is being recommended for the patient’s medical condition. (6)

Shahvisi further claims patients often simply rely upon physician authority for personal understanding; in such cases, there exists a wide – and ethically undesirable – epistemic disparity between physician and patient. (6) But even in such cases, the health practitioner should, in principle, be able to explain the treatment to the patient if so requested, or at least be able to provide a helpful referral.

Shahvisi argues, “Alternative medicine treatments fundamentally cannot be understood by anybody, including patients and physicians, because these modalities do not draw upon plausible physical causes, and may rely upon implausible mechanisms (e.g., acupuncture, homeopathy) or supernatural interventions (e.g., faith healing).” (6) In this way, Shahvisi concludes that without such knowledge or understanding, informed consent is impossible, and it is unethical for medical professionals to recommend or endorse alternative medicine treatments. (6)

Safety and CAM

Safety is central to all healthcare practitioners and is an area where those using and recommending CAM should work together to achieve consensus regarding data collection and sharing. (7) Systems for reporting safety issues are not only important to obtain information, but should also be used as a tool to enhance learning, advance quality improvement, and to decrease errors linked to patient care. (7) Evidence of safety is an urgent priority for CAM, as a growing number of CAM professions achieve statutory or voluntary regulation. (7)

The potential safety risks of CAM include: intrinsic adverse effects (related to errors in treatment via a practitioner or self-medication); interaction with pharmaceuticals/other CAM and extrinsic effects due to lack of standardization; contamination; substitution; adulteration; incorrect preparation/dosage or inappropriate labeling; and lack of quality control, licensing, regulation and misrepresentation. (7) Further risks may arise when CAM is used as an alternative to medical treatment, as an issue commonly of concern is the risk of interaction between CAM and conventional medication, especially for herbal medicines and supplements, which is often aggravated by lack of communication between clinicians, CAM practitioners, and patients. (7)

However, a brief overview of available data for some specific therapies suggests the risk of major adverse events with manual therapy, acupuncture, and homeopathy is low, and evidence suggests that adverse effects in acupuncture are declining, perhaps due to more rigorous training and practice. (7) With that said, there is a lack of standardized, routine, and widely available data on safety across the CAM professions. (7) “Competency should be covered by each professional association’s terms of acceptance onto professional registers, and assured through education.” (7) Ultimately, evaluations of efficacy and effectiveness by medical researchers holds the promise of minimizing adverse effects and maximizing the usefulness of those CAM therapies that prove effective. (4)

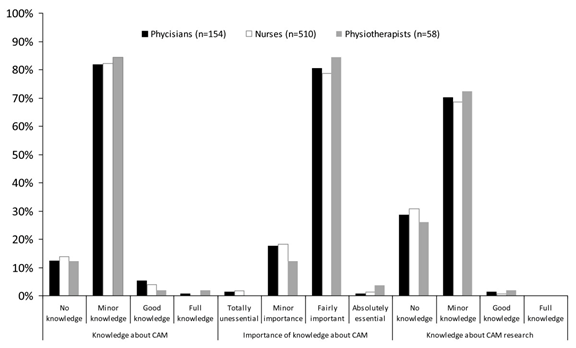

From a Nurse’s Perspective

In a study where information on nurses’ demographics, knowledge, attitudes, and professional use of CAM was obtained using a self-administered questionnaire, over one-fifth of the nurses rated their attitudes towards CAM as very positive, 36.6% as slightly positive, while only 2.5% had a very negative attitude towards CAM. (8) Almost 50% of nurses were using CAM for patients, with mind-body interventions being the most common form of CAM domain used in practice at 31.4%.

It is interesting to note that while only 59% of nurses were positive about CAM, more than 60% of them had very little or no knowledge of CAM, yet they all were open towards CAM use in the in-hospital context. (8) This study raised an important point as it found a positive association between the nurses’ knowledge and their attitudes towards CAM. Nurses’ positive attitudes towards CAM use illustrate they are open for further integration of clinically approved CAM therapies into their patients’ care.

The Acceptance of CAM in Educational Programs

The widespread use of CAM requires that health professionals have the required knowledge to better advise their patients. At one point in history, CAM was defined as, “Interventions neither taught widely in medical schools nor generally available in hospitals,” yet medical schools and programs are starting to respond to the increasing demand by including CAM in their curricula. (9) In realizing that to provide effective health care, promotion of health, to prevent illness, and foster an improved patient-practitioner partnership, health professionals, in general, should become an informed consultant, and be able to provide educated advice about CAM to their patients. (9) Using CAM principles to educate and engage inter-professional learners enables individuals to collaborate more effectively, share problem-solving and decision-making tasks, and integrate disparate knowledge structures. (10)

The increased need for the inclusion of CAM instruction into the mainstream undergraduate education even includes pharmacists and Pharmacy education. The study by James and Bah was designed to describe pharmacy students awareness, use, attitude, and perceived need for CAM education, and at the same time, determine how the socio-demographic variables influence these descriptive outcomes.

A descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted among 90 undergraduate pharmacy students at the College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of Sierra Leone, using a structured questionnaire. (11) Pharmacy students in Sierra Leone were aware of and had used at least one of the CAM modalities, and almost two-thirds of students considered the CAM modalities they have used to be effective and not harmful. (11)

Interestingly enough, the media, at 58.9%, was the most frequent source of information about CAM. (11) Nearly all students agreed CAM knowledge is important to them as a future pharmacist and that CAM should be included into the Pharmacy curriculum. (11) The overwhelming endorsement by pharmacy students for CAM education was not affected by year of study, student gender, religion, or age group. (11) The overall positive attitude toward CAM among Pharmacy students in this study resonates with many other studies which assess students’ attitudes toward CAM globally. This study, among others, will inform and guide the development and implementation of CAM instruction within undergraduate education.

Building Professional-Patient Relationships

The study by Caspi et al. explored and described patients’ decision paths related to CAM use. (12) The study found that different patients utilize different decision-making paths to arrive at healthcare-related decisions. One group required multiple sources, involving friends, family, close associates, the Internet, and a logical explanation before making decisions to use either CAM. (12) Regardless, logic and evidence were tempered by the participants’ belief system, values, and philosophical views, and they were comfortable with uncertainty. (12)

Contrastingly, some participants consistently trusted their physician to make correct treatment choices, and they appeared to be willing to experiment with treatment modalities once the options were identified, but allopathic physicians seemed to be the ultimate authority regarding health information and disease treatment. However, if they had exhausted allopathic means and perceived their situation to be hopeless, most were willing to try alternative treatments as a last resort. (12)

This study stressed that healthcare providers should be knowledgeable, as well as sensitive, to the different decision-making paths of their patients and be sensitive to the patient’s desire and belief system without judgment.

Ethnic Minorities CAM Use

Despite the population growth of minorities, there is a gap in the current literature available on CAM use by adults of nonwhite racial backgrounds. (13) With this in mind, the study by Graham et al. aims to determine the prevalence of CAM use in ethnic minority populations; to identify how race/ethnicity influences the use of CAM, to examine the reasons for use, and rates of disclosure to medical professionals. (13)

The researchers analyzed data from the Alternative Health Supplement to the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), including information on 19 different CAM therapies. (13) A limitation of this study is little information was available on items such as health beliefs, customs, and attitudes towards CAM. This suggests the value of interdisciplinary collaboration and multi-method studies to increase the knowledge base and effectiveness of CAM use and rationales across populations.

Ultimately, the successful delivery of health services to minorities must include increased awareness and appreciation for the cultural context of their CAM use by examining health belief systems and their potential effect on health behaviors and outcomes. (12) A greater understanding of their use of CAM may also aid in addressing health disparities and inequalities. (12) Further research is needed among minority populations to provide us with a greater understanding of their use of CAM to serve their needs within the current health system.

What Our Patients May Not Be Telling Us and Why

Despite the frequent use of CAM, discussion with health providers is infrequent. Previous international publications found communication between patients and the caregiver regarding CAM was perceived as rare. (14) Perhaps the healthcare provider’s lack of knowledge discourages them from bringing up the subject and having to face questions they may not feel comfortable, capable, or even qualified to answer.

It is also very possible patients avoid discussion of CAM out of fear of criticism from their healthcare provider. Graham et al. estimated previous studies have consistently shown nondisclosure rates at about 63-72%, though their study was the first to show ethnic differences in disclosure rates. (13) The researchers also found even without the language barriers certain minorities face, English-speaking, nonwhite patients may not inform their doctors of nonconventional treatments because they are embarrassed to discuss them, or feel the physician will view them as quackery or unsophisticated, or think them irrelevant. (13)

This highlights the need for proactive inquiry among all healthcare professionals to ask their patients about their CAM use. Additionally, multi/interdisciplinary (e.g., anthropology, folklore, botany, ethnobotany, and sociology) collaboration is critical to designing culturally appropriate survey instruments to avoid unconscious ethnocentric bias in categorization and definitions. (13)

If So Many Patients are Already Using CAM, Why is it Not Considered Mainstream Healthcare?

A study by Maha et al. explored academic doctors’ views of CAM and its role within the National Health Service. The majority of general practitioners (GPs) from the qualitative study implore the use of a limited range of more mainstream therapies, notably acupuncture, chiropractic, and osteopathy; these subjects claimed they practiced more holistically, as their patients easily and openly expressed their concerns. (15)

The main rationale amongst the doctors who were negative about CAM was the perceived absence of a strong evidence base, and the doctors lacked the knowledge to make an informed judgment. (15) This echoes wider views expressed by health professionals in debates about CAM. There was a consensus about the need to include CAM within the undergraduate medical curriculum, as well as, the approval that some evidence is available to show CAM as effective or helpful for their patients. (15)

Themes in this study merit further examination in a larger qualitative study, with a broader sample of doctors from a more diverse range of settings, to produce more generalizing results, though the study is appropriate in exploring a specific population and specific CAM therapies. Since all participants had an academic role, the findings of the second study may over-emphasize the importance of scientific evidence to doctors, undermining the acceptance of CAM within mainstream healthcare systems. (15)

Research Gaps: The Critical Need for More Research

There have been several points made in this review which have highlighted the gaps in research and the need for more research around CAM. As there is obvious recognition more patients are requesting CAM is increasing despite the limited evidence base, increased patient demand becomes a key driver for greater integration of CAM within conventional medicine. However, more rigorous trend data from epidemiologic surveys are necessary to evaluate the assumption of future growth of CAM therapies on the basis of evidence of past trends. (4)

Additionally, although not captured in the study by James & Bah, student preferences with regards to the mode of learning, which academic year(s) CAM should be introduced in, as well as faculty members’ attitude and competency to teach CAM modules, are key issues to be considered for the inclusion of CAM into any health field curriculum. (11) A possible limitation to this and many other studies are the students’ true beliefs and perception about CAM, and the verification of these responses. However, these studies do give baseline information with regards to the awareness, use, and attitude of CAM among healthcare students in general.

Bjerså et al., as well as Hirschkorn and Bourgeault, found obstacles to gaining knowledge about CAM were lack of time and a perceived difficulty to access research results. (14, 16) According to their study, knowledge about CAM research was very low or non-existent. (14) Despite the low access to research results and low knowledge level, CAM research was criticised for being biased and of low quality. (14) It becomes clear just how vital it is to create evidential research to judge whether to use therapies or not adequately.

This may explain why over 60% of the participants thought more resources should be addressed to CAM research and more research should be addressed to measure current consumption, effect, risks and adverse effects, and the economic dimensions in CAM usage. (14) Ultimately, the results of their study showed registered healthcare workers felt possessing knowledge regarding CAM was of importance, which is widely supported by other international publications which showed healthcare workers want to learn more about CAM.

Similarly, teaching students how to find and evaluate the evidence for the safety and efficacy of CAM would undoubtedly inspire a needed collection of evidence for the proper recommendations and use of these therapies for the future. The goal here is to encourage the additional skills of openness, sensitivity to cultural influences and beliefs, communication, and critical appraisal of the literature of CAM in an effort to improve a health professional’s knowledge of CAM practices and their place in patient care. (3)

Understanding the barriers all patients, and especially minorities, face regarding nondisclosure of CAM use to their healthcare providers is crucial. Research is also needed to develop more culturally sensitive questionnaires. Additionally, to better understand how decision-making processes work for different patients and how healthcare providers may recognize these differences, more research that cuts across disease processes and geographical areas needs to be conducted. Consequently, further studies to understand the pattern of CAM use among patients and the general public will inform the development and implementation of evidence-based CAM instruction in the faculties of educational programs. (11)

Differing opinions about the adequacy of research to verify the safety and efficacy of specific therapies must be acknowledged, as a medical professional’s openness to CAM is largely swayed by their responsibility to provide care backed by extensive evidence-based research. (9) Because some of these products have been known to have associated adverse effects, including drug interactions and toxicity, it is imperative this barrier of knowledge be broken and approached proactively by the dental community at large. (17) After all, what may be alternative for one individual could be conventional for another.

Conclusion

It becomes clear individuals, from patient to practitioner, are drawn to CAM out of a desire for a more ‘holistic’ approach, and CAM will play a leading role in 21st-century health care, and specifically in self-care. (8) It is assumed the growing use of CAM on the fringes of allopathic medicine, and their growing popularity among medical practitioners may cause more CAM therapies to be integrated into mainstream healthcare. (8) The emergence of CAM in our healthcare environment requires that more information and education to all medical professionals are provided to integrate CAM into the conventional health care system successfully.

There has been a clear willingness and receptivity demonstrated by the majority of health professionals to deliver, promote, or to permit the administration of certain CAM therapies. (8) Finding ways to incorporate CAM therapies in a clinical setting as well as in educational settings speaks to the professionals who seek to advance their profession, as well as those who also wish to stay current with what is available and being used by their patients. Healthcare professionals, patients, and the healthcare system can only benefit by bridging the gap between alternative eastern and traditional western modalities of medicine.

Resources for More Information

An excellent resource for the latest research and information about CAM therapies for health professionals and patients is the NCCAM, a component of the National Institutes of Health. “NCCAM’s mission is to explore complementary and alternative healing practices in the context of rigorous science, train CAM researchers, and disseminate authoritative information to the public and professionals. It provides timely and accurate information about CAM research through their Website, fact sheets, and publication databases.” (2)

SEE ALSO: Oil Pulling: Is it Effective?

DON’T MISS: Erythritol: The Other Sugar Alcohol

References

- Posadzki, P., Alotaibi, A., & Ernst, E. (2012). Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by physicians in the UK: A systematic review of surveys.Clinical Medicine (London, England), 12(6), 505-512. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235365228

- Thobaben, M. (2009;2008;). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies: Which are your clients using? Home Health Care Management & Practice, 21(3), 211-213. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1084822308327963

- Berman BM. Complementary medicine and medical education: Teaching complementary medicine offers a way of making teaching more holistic. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2001; 322(7279): 121-122. Retireved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1119400/

- Kessler, R. C., Davis, R. B., Foster, D. F., Maria I. Van Rompay, Walters, E. E., Wilkey, S. A.. . Eisenberg, D. M. (2001). Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the united states.Annals of Internal Medicine, 135(4), 262. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11511141

- Kadam, A., Prasad, B. S., Bagadia, D., & Hiremath, V. R. (2011). Effect of Ayurvedic herbs on control of plaque and gingivitis: A randomized controlled trial. Ayu, 32(4), 532–535. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8520.96128

- Smith, K., Ernst, E., Colquhoun, D., & Sampson, W. (2016). ‘Complementary & alternative medicine’ (CAM): Ethical and policy issues.Bioethics, 30(2), 60-62. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291951888

- Robinson, N., Lorenc, A., & Lewith, G. (2011). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) professional practice and safety: A consensus building workshop.European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 3(2), e49-e53. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/european-journal-of-integrative-medicine/vol/3/issue/2

- Shorofi, S. A. (2011). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among hospitalised patients: Reported use of CAM and reasons for use, CAM preferred during hospitalisation, and the socio-demographic determinants of CAM users.Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17(4), 199-205. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21982133

- Maizes, Victoria, David Rakel, and Catherine Niemiec. Integrative Medicine and Patient-Centered Care. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing5.5 (2009): 277-89. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19733814

- S., Alder. Creating an interprofessional curriculum in integrative medicine for medical, nursing, pharmacy, and dentistry students: curriculum mapping strategies. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine Journal.June 12, 2012. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257874477_P0305_Creating_an_interprofessional_curriculum_in_integrative_medicine_for_medical_nursing_pharmacy_and_dentistry_students_curriculum_mapping_strategies

- James, P. B., & Bah, A. J. (2014). Awareness, use, attitude and perceived need for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) education among undergraduate pharmacy students in sierra leone: A descriptive cross-sectional survey.BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 14(1), 438. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25380656

- Caspi, Opher, Mary Koithan, and Michael W. Criddle. 2004. Alternative medicine or “alternative” patients: A qualitative study of patient-oriented decision-making processes with respect to complementary and alternative medicine. Medical Decision Making24 (1): 64-79. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0272989X03261567

- Graham, R. E., Ahn, A. C., Davis, R. B., O’Connor, B. B., Eisenberg, D. M., & Phillips, R. S. (2005). Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: Results from the 2002 national health interview survey.Journal of the National Medical Association,97(4), 535-545. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15868773

- Bjerså, K., Stener Victorin, E., & Fagevik Olsén, M. (2012). Knowledge about complementary, alternative and integrative medicine (CAM) among registered health care providers in swedish surgical care: A national survey among university hospitals.BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 12(1), 42-42. Retrieved from https://bmccomplementalternmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6882-12-42

- Maha, Nita, and Alison Shaw. 2007. Academic doctors’ views of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and its role within the NHS: An exploratory qualitative study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine7 (1): 17-. Retrieved from https://bmccomplementalternmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6882-7-17

- Hirschkorn KA, Bourgeault IL: Conceptualizing mainstream health care providers’ behaviours in relation to complementary and alternative medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (1): 157-170. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15847969

- Little, James W. Complementary and alternative medicine: impact on dentistry. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontics. August 2004. Volume 98 , Issue 2 , 137 – 145. Retrieved from https://www.oooojournal.net/article/S1079-2104(04)00348-8/abstract