Dental hygienists are well-versed with oral cancer and the importance of early detection, but what about those lesions that are in limbo ─ the ones that are precancerous or have the potential to become precancerous?

What are premalignant oral disorders or potentially malignant oral disorders? In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined oral premalignant disorders as “clinical presentations that carry a risk of cancer development in the oral cavity, whether in a clinically definable precursor lesion or in clinically normal mucosa.”1 In other words, these lesions can be found in what we would consider being “healthy” tissues and can also be what oral pathology report dictates for an existing lesion.

Here is a helpful flow chart from the American Dental Association (ADA) on potentially malignant disorders.2 Both leukoplakia and erythroplakia lesions are considered to have the potential to become malignant and have high occurrences of epithelial dysplasia upon biopsy.1

Dysplasia is of extreme clinical importance when discussing potentially malignant oral disorders. “Dysplasia,” according to one article, “is the step preceding the formation of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in lesions which have the potential to undergo dysplasia.”3 The article goes on to state that SCC is the most common malignancy found in the oral cavity.3

What is Leukoplakia?

Several different definitions of “oral leukoplakia” have emerged over the years. In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined leukoplakia as “A white patch or plaque that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease.”4 In 1997, the WHO removed “any other definable disease” and replaced it with “any other definable lesion.” The most recent definition of oral leukoplakia from the WHO is from 2005 when the organization defined it as “A white plaque of questionable risk having excluded (other) known diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer.”4

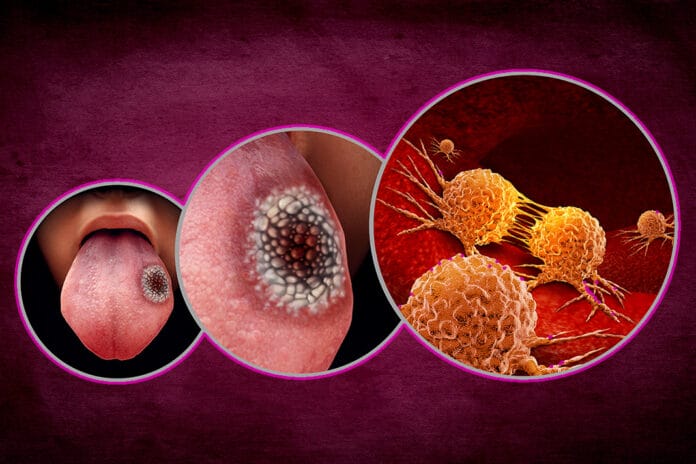

Clinically, oral leukoplakia appears as a white lesion that can have a wrinkled or “dry, cracked mud” surface appearance (see image 1).5 The areas where these lesions can most commonly be found are the buccal mucosa, both the hard and soft palates, lateral borders, and ventral surface of the tongue.5

According to the ADA, not all lesions that are determined as leukoplakia will transform into a premalignant or malignant lesion. The risk, though, is great enough that clinicians must remain vigilant.

Men over the age of 50 are most at risk for developing leukoplakia compared to their female counterparts.4 The exact cause for oral leukoplakia is unknown. Some risk factors, though, have been linked to the condition, including sanguinaria, alcohol, tobacco, betel quid, and trauma.5

It is important to note that oral lichen planus remains controversial as to whether it is a true potentially malignant disorder, so this article will not focus on it.

Types of Oral Leukoplakia

The two main types of oral leukoplakia are defined as either homogeneous or nonhomogeneous. Homogeneous leukoplakia is white in color throughout the entirety of the lesion, has well-defined margins, and a nonulcerated surface.

Differing from their homogeneous counterparts, nonhomogeneous leukoplakia lesions are not white in their entirety (see image 2). These lesions also display areas of erythroplakia and can include spots that appear erosive, ulcerated, nodular, as well as display another subset of oral leukoplakia, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL).1,4,5

PVL most commonly occurs in women over the age of 60. Clinically, these lesions appear as white patches with well-defined borders, a rough surface that has ridges or grooves on it and grows in an outward direction. Due to their surface appearance and fingerlike projections, these lesions are sometimes described as being “wart-like.”5,6

According to one source, PVL can exhibit both the classic verrucous/nodular pattern but may also include areas that are homogeneous/fissured and erythroplakia areas within the same lesion.1 While all leukoplakia lesions are noteworthy, PVL lesions are of extreme importance because it is estimated that their potential for malignancy is between 70 and 100%.1 These lesions have a high recurrence rate, estimated at 85%, while all other oral leukoplakia have a low recurrence rate estimated at 5-10%.5

What is Erythroplakia?

According to the American Cancer Society, erythroplakia can be described as a “flat or slightly raised, red area that often bleeds easily if it’s scraped.”6 The surface of these lesions can also have a bumpy or pebbled appearance to them.5

While erythroplakia is considered to be the least common of all potentially malignant lesions, they are of extreme importance because it is estimated that up to 90% of these lesions display squamous cell carcinoma (see image 3), carcinoma-in-situ, or epithelial dysplasia.1

What Can Dental Hygienists Do?

The Oral Cancer Foundation’s position on when a lesion denotes a further evaluation is as follows: “Any sore, discoloration, induration, prominent tissue, irritation, hoarseness, which does not resolve within a two-week period on its own, with or without treatment.”7

According to the foundation, any of the above signs or symptoms lingering past the two-week period should prompt further treatment and examination. This may also include a referral to another dental professional.7 The foundation also maintains that the only way to have a definitive diagnosis of any lesion is via scalpel biopsy.7 If your office does not perform surgical biopsies, you may need to refer these patients to an oral surgeon, periodontist, or oral pathologist for further evaluation.

Hygienists understand the importance of detailed notes and how intraoral photographs can only enhance our description of a lesion. Taking a photo of a lesion can be beneficial in so many ways. Perhaps most importantly, it serves as a visual baseline for the area. It can also be used to educate patients, and they may be more willing to comply with the recommended treatment or referral if they can actually see the lesion you are trying to explain to them. It can be very helpful to capture the lesion and surrounding tissue so that you have something “normal” when comparing. Other practitioners the patient may be referred to will be very grateful to have a picture of the lesion when it was first noticed.

Noting every detail of the lesion in the patient’s chart is just as valuable as a photo: the size, shape, borders (are they irregular, sharp and easily outlined, or blended and difficult to differentiate where the lesion begins and ends), color(s), texture (pebbled/smooth/raised/flat, etc.). Don’t be afraid to use several descriptive words and details; it is always better to have too much information than not enough.

Patients we encounter with potentially malignant lesions may require close follow-up care, more frequent visits, as well as surgical procedures (biopsy). Patients may not always be receptive to adding more visits to their already busy schedules as well as bristle at the potential out-of-pocket costs they may encounter. To combat this, we can encourage them that while their lesion today is not “cancerous,” it has the potential to become malignant and, for that reason, we must remain vigilant.

Need CE? Check Out the Self-Study CE Courses from Today’s RDH!

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Woo, S.B. Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Premalignancy. Head Neck Pathol. 2019 Sep; 13(3): 423–439. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6684678/pdf/12105_2019_Article_1020.pdf

- Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation of Potentially Malignant

Disorders in the Oral Cavity: A Report of the American Dental Association. (2017). American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/10870a_chairside_guide_oralcancer_final.pdf - Homayoni, S., Kargahi, N., Razavi, S.M., Shirani, S. Epithelial Dysplasia in Oral Cavity. IJMS. 2014; 5(39). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4164887/pdf/ijms-39-406.pdf

- Waal, I.V.D. Oral Leukoplakia, The Ongoing Discussion on Definition and Terminology. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Buca. 2015; 20(6): e685-692. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4670248/pdf/medoral-20-e685.pdf

- Anbari, F., Baharvand, M., Jafari, S., Mortazavi, H., Rahmani, S., Safi, Y. Oral White Lesions: An Updated Clinical Diagnostic Decision Tree. Dent J. 2019; 7(1): 15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6473409/

- What Are Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancers? (2021, March 23). American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/about/what-is-oral-cavity-cancer.html

- The Role of Dental and Medical Professionals. (n.d.). The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/dental/role-dental-medical-professionals/