Dental hygienists are among the 5.6 million workers in health care and related occupations who are at risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens and other potentially infectious material (OPIM) such as saliva in dental procedures.2 Dental professionals handle dental scalers, burs, anesthetic needles, orthodontic wire, and other hazardous materials daily.

Dental facilities should have a clear protocol for sharps injuries to ensure employees’ immediate care and long-term health after an exposure.

Exposure Risk for Dental Hygienists

The American Dental Association defines an exposure incident as any eye, mouth, mucous membrane, non-intact skin, or other parenteral contact with blood or OPIM.3 Bloodborne pathogens are infectious microorganisms in human blood that can cause diseases such as HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.2

A study in the Journal of the American Dental Association found blood present on 16% of a needle surface and 39% within the lumen of a needle after local anesthetic administration. The risk of transmission of HIV, HCV, and HBV are 0.3%, 3%, and 30%, respectively.5 An estimated 600,000 to 800,000 needlestick or percutaneous injuries among healthcare workers occur annually, and approximately half of those injuries go unreported. The top two reasons given by healthcare workers who did not report a sharps injury were perceived lack of time and estimation that transmission risk was low.7

Needlestick injuries examined at a dental specialty university hospital over 12 academic years found that 63% of injuries happened in the afternoon: 27% were from anesthetic needles; 10.2% from scalers for hand use; 10.2% from suture needles; and 8.37% from ultrasonic scalers. Other sources were endodontic files, orthodontic wire, dental burs, and explorers.6

OSHA Standards

OSHA released the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard in 1991, requiring employers to establish a written exposure control plan to eliminate or minimize employee exposure. Additionally, employers must implement engineering controls to isolate or remove bloodborne pathogen hazards from the workplace. The most common engineering control in dental offices is the annual training of staff in the safe handling and disposal of dental sharps.

The Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act was signed into law in 2000, and the law sought to further reduce healthcare worker exposure to bloodborne pathogens by imposing additional requirements upon employers. One requirement is that employers must maintain a sharps injury log. The log should contain a record of the type and brand of device involved in the incident, department, or work area where the incident occurred and an explanation of how the incident occurred.

The federal OSHA recordkeeping rule does not require dental offices to maintain a sharps injury log, but there are 22 OSHA-approved state plans that may require this record.2,8

OSHA’s final rule for occupational exposure requires employers to make a confidential medical evaluation immediately available and follow-up to an event of an employee reporting an exposure incident.3 Potential exposure must include two factors: infectious body fluid and portal of entry (percutaneous, mucous membrane, cutaneous with non-intact skin).9

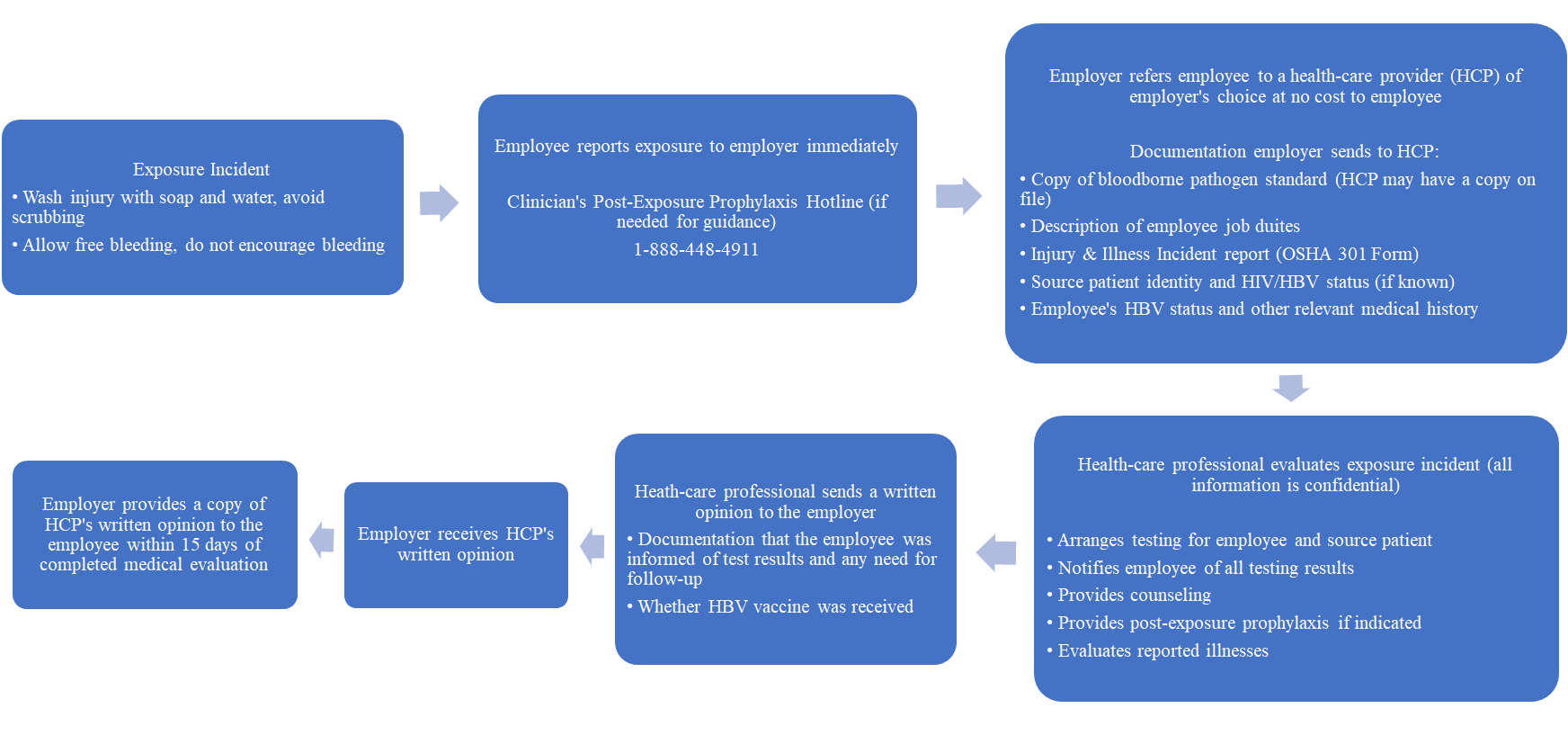

7-Step Exposure Protocol Guide

- Employees should report the incident to their employer immediately. If HIV post-exposure prophylaxis is indicated, it should be initiated within one to two hours of exposure.

- Employer will refer the employee to a licensed healthcare provider of the employer’s choice at no cost to the employee.

- Dental employers, as a requisite for employment, may need a record of medical history pertaining to vaccination status or other pertinent medical information such as annual tuberculosis testing. It is required by the Americans with Disabilities Act to keep employee medical records confidential and separate from a regular personnel file for the duration of the employee’s employment plus 30 years. Employees have the right to delay testing for up to 90 days or to refuse testing altogether; in this instance, the dental employer should document the refusal for the employee’s medical record.2

A dental employer must prepare the following documents to send to the healthcare provider and for the employee’s confidential medical record:

- Injury and Illness Incident Report OSHA 301 Form

- Description of employee job duties

- The ADA recommends sending a copy of the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standard (healthcare provider may have a copy on record)

- Relevant employee medical records and hepatitis B vaccination status

- If known and permitted by law, the identity and blood test results of the source patient

The dental employer must identify and document in writing the source of an exposure incident. The source patient should be contacted, if known, and asked to be tested for HIV, HBV, and HBC. The employer should report those results to the exposed employee.

Dental hygienists and their employers may understandably be concerned with alarming the source patient by requesting a blood test. Explain to the source patient that testing helps an exposed employee and their healthcare provider make medical and testing decisions while using precaution to prevent transmission. Knowing the health status of the source patient may also help to alleviate some anxiety for the exposed employee. It should be documented if the source patient does not consent to testing.

- Medical services must be made available free of charge to an employee who has had an exposure incident:

- Collection and testing of employee’s blood to establish baseline HBV and HIV serological status. All lab tests must be performed by an accredited lab.

- The healthcare provider will provide counseling concerning infection status, interpretation of results, discuss the potential risk of infection, and any need for post-exposure prophylaxis.

- Post-exposure prophylaxis may require follow-up visits to the healthcare provider for serial blood tests and monitoring of any prescribed medications.

- Evaluation of reported illness. The healthcare provider will need to evaluate any reported illness to determine if symptoms are related to HBV or HIV to ensure early medical evaluation and treatment.

This does not mean the dental employer is responsible for the cost of the treatment should the employee develop a disease. Long-term treatment may be covered under disability insurance or workman’s compensation.3

- The healthcare provider should send a copy of their written opinion to the dental employer. This should contain documentation that the exposed employee was informed of test results and the need for further follow-up as well as hepatitis B vaccination status. Any other findings or diagnoses are confidential.

- When the dental employer receives the healthcare provider’s written opinion, the original goes into the employee’s confidential medical file.

- The employer should provide a copy of the healthcare provider’s written opinion to the exposed employee within 15 days of receiving it from the healthcare provider.

Independent Contractors

Dental sharps injuries support the case against working as an independent contractor because dental hygienists may find themselves in a muddled area of assigning financial responsibility after an injury. Dental hygienists who do choose to be misclassified according to the IRS and work as independent contractors should have a clear understanding of who is financially responsible for testing and treatment in the event of an exposure. If the dental hygienist contracts through a temp agency, the dental employer and agency may have shared responsibility depending on what their contract states.

Generally, the agency is responsible for follow-up and requiring up-to-date vaccination status unless the contract states the dental employer will cover it. A dental hygienist who does not work through a temp agency may want to develop a contract outlining financial responsibility in the event of an exposure.3

Dental Sharps Injury Prevention

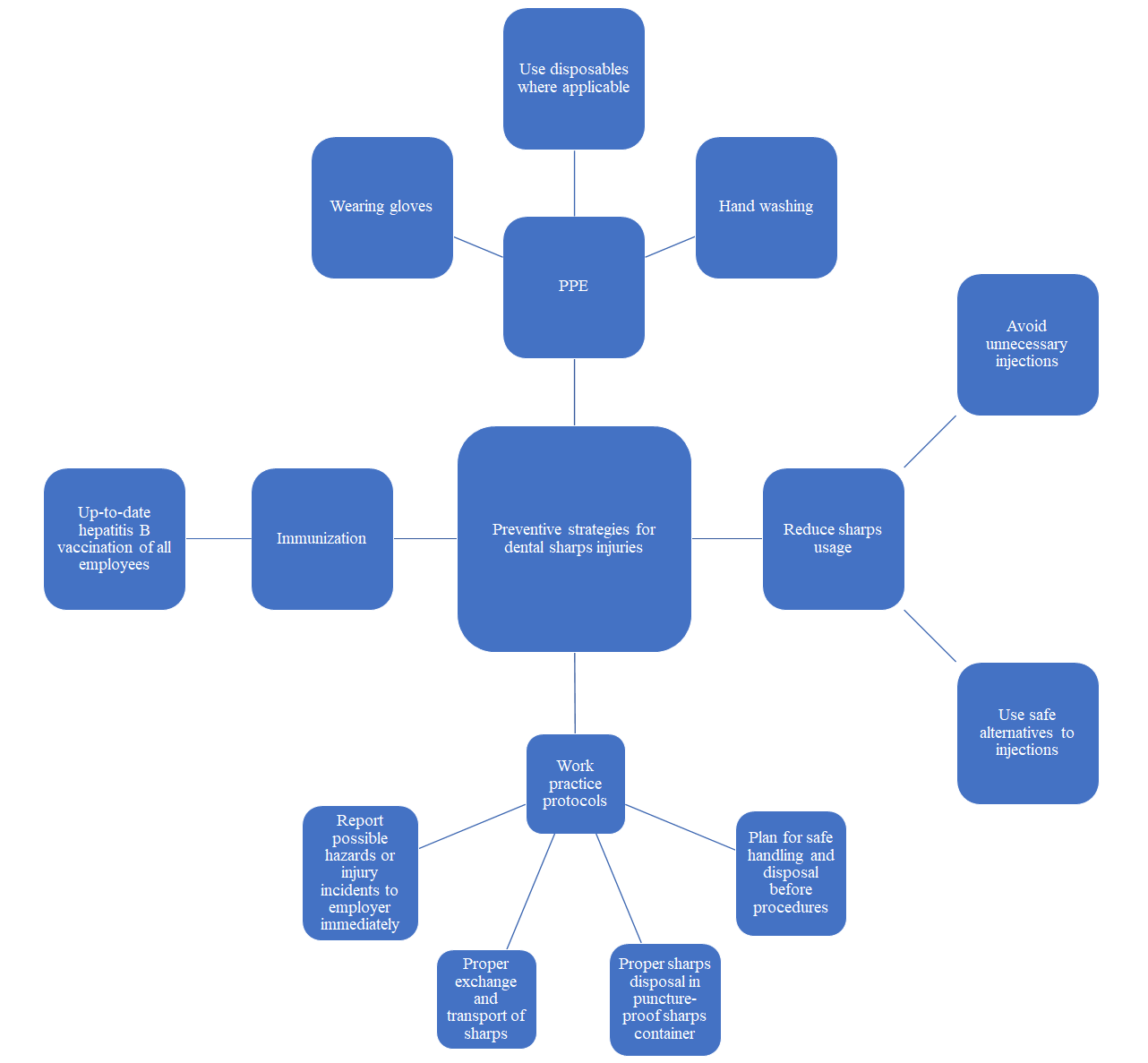

Dental employers should ensure the following elements of a sharps injury prevention program are included:

- Analyzing sharps-related injuries to identify hazards and injury trends.

- Ensure employees are properly trained in the safe use and disposal of dental sharps.

- Promote safety and awareness in the work environment.

- Modify practices that pose an injury risk.

- Establish procedures for reporting and timely follow-up of all dental sharps injuries.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of prevention efforts and feedback from employees.1,7

Dental employees may implement these additional safety measures:

- Avoid the use of needles where safe alternatives are available.

- Plan for safe handling and disposal of sharps before any procedure that requires their use.

- Dispose of needles promptly in approved sharps disposal containers.

- Report all sharps-related injuries immediately to ensure appropriate follow-up care.

- Report hazards (i.e., an over-filled sharps container) to the dental employer.

- Participate in bloodborne pathogen training and follow recommended infection prevention practices, including up-to-date hepatitis B vaccinations.1,7

Dental hygienists are trained in safety standards regarding the assembly and disassembly of syringes and proper disposal of needles and anesthetic cartridges. Still, dental needlestick injuries account for the highest proportion of all types of exposures as 38% occur during use and 42% occurring after use and before disposal.

The hand used to retract tissue is most likely to endure an injury.7 A modified retraction technique is recommended. The clinician first palpates the tissue to evaluate landmarks, then removes their hand to retract the tissue with a mouth mirror, and proceeds with the injection.4

OSHA’s standard requires immediate disposal of needles in an approved sharps container without recapping, bringing the likelihood of a needlestick while recapping from 10%-25% to 5%.7 However, in some states, it is still an error for a dental hygienist not to recap during a board exam.

Dental hygienists may use the one-handed scoop method and should use forceps to remove the needle from the syringe after use. Explore other safety options, including clinical cassettes with a needle cap holder, needle sheath props, and self-sheathing systems. Check procedure trays and waste materials for sharps before handling, and transport reusable sharps in a closed container.4,6

Need CE? Check Out the Self-Study CE Courses from Today’s RDH!

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Bindra, S., Ramana Reddy, K.V., Chakrabarty, A., Chaudhary, K. Awareness About Needle Stick Injuries and Sharps Disposal: A Study Conducted at Army College of Dental Sciences. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 2014; 13(4): 419-424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-013-0526-3

- Bloodborne Pathogens and Needlestick Prevention. (n.d.). Occupational Health and Safety Administration. https://www.osha.gov/bloodborne-pathogens

- Employer Obligations After Exposure Incidents OSHA. (n.d.). American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/osha-standard-of-occupational-exposure-to-bloodbor#Step

- Fa, B.A., Cuny, E. Preliminary Evidence Supports Modification of Retraction Technique to Prevent Needlestick Injuries. Anesthesia Progress. 2016; 63(4): 192-196. https://doi.org/10.2344/15-00038.1

- Kotze, M. J., Labuschagne, W. A Method of Determining the Presence of Blood On and On a Dental Needle After the Administration of Local Anesthetic. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2014; 145(6): 557-562. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.2014.14

- Matsumoto, H., Sunakawa, M., Suda, H., Izumi, Y. Analysis of Factors Related to Needlestick and Sharps Injuries at a Dental Specialty University Hospital and Possible Prevention Methods. Journal of Oral Science. 2019; 61(1): 164-170. https://doi.org/10.2334/josnusd.18-0127

- Preventing Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Settings. (1999). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2000-108/

- Tatelbaum, M.F. Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act. Pain Physician. 2001; 4(2): 193-195.

- PEP Quick Guide for Occupational Exposures. (2020). University of California: National Clinician Consultation Center. https://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/pep-resources/pep-quick-guide-for-occupational-exposures/